Low-income Marylanders are already getting less supplemental food income from the government than during the pandemic, now the debt ceiling deadline could put them in further jeopardy.

In March, Maryland stopped paying its emergency Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) rates in accordance with the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

The emergency funding was supposed to help people pay for food and extra items they may need during the pandemic, but now with those funds gone, experts are concerned that the gap between food pricing and benefits could deal a heavy blow to low-income residents.

"Many people are going to turn to pantries and the food banks, but there's no way that they can make up that difference,” said Michael J. Wilson, director of Maryland Hunger Solutions. “It is too big for them to be able to make it up in the charitable space.”

The average SNAP participant lost $82 a month when the allotments ended. Currently, about 600,000 Marylanders are receiving those benefits.

That comes out to about $69 million less in federal funding per month compared to the pandemic.

Wilson says low-income families are now receiving a similar stipend from before the pandemic, however the landscape is different.

According to the Department of Agriculture, food prices are expected to increase by 6.2% in 2023.

The USDA only raises benefits once per year to adjust for inflation, meaning that costs can often outpace SNAP allotments.

Wilson says the change in allotments will have a larger impact on the economy as a whole.

“If you run a Safeway grocery store in Baltimore City, you are worried about what it means,” he said. “We're going to take a billion dollars out of our state's food economy. It's not just going to hurt low-income folks, though, clearly low-income people are going to suffer. But it's going to impact grocery stores and farmers markets and corner stores.”

Now the stakes are even higher as the federal government could default on its loans if it doesn’t come to an agreement by June 5.

The situation is unprecedented for the United States, but a default could mean that the country is unable to pay federal benefits if the default drags on.

That means possible stoppages for federal pay, social security and benefits like SNAP.

“If you want to have a debate about these other debt issues, let's have that,” he said. “But let's not do it in the midst of holding folks hostage to whether or not they're going to be able to have food for themselves and their families.”

The agreement reached by President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy would raise the debt ceiling and avert those doomsday situations.

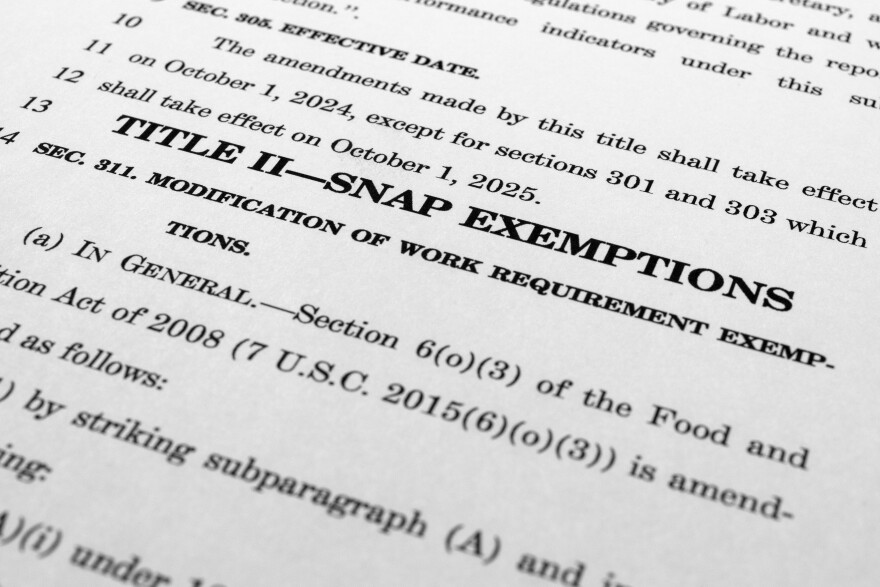

However, one of the concessions from the White House is increased work requirements for programs like SNAP.

Currently, people 18 to 49 who use SNAP are required to work or volunteer 80 hours per month. The debt ceiling deal would expand that age range to 54.

Even though McCarthy and Biden have found common ground, it doesn’t mean the debt ceiling agreement is a done deal.

Both houses of Congress still need to pass the bill before the deadline.