We team up with Arlo Iron Cloud of KILI Radio, Voice of the Lakota Nation, for this listening tour of The Pine Ridge Reservation, a 50 by 100 mile stretch of land in South Dakota that's home to the Oglala Lakota people. In this episode, we meet a radio producer, a hip hop artist, a medicine man, a home builder, a tribal government leader, a powwow organizer, a painter, and a philosopher who’s chosen to live alone in a house with no electricity and no running water.

TRANSCRIPT:

Multiple Voices: From WYPR and PRX, it’s a special edition of Out of the Blocks. From Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, it’s one neighborhood, everybody’s story.

I want you to meet women’s rights activists, students, teachers. I want those people that aren’t always heard to be heard.

We’re on this reservation that’s about fifty by a hundred miles. But yet, we’re surviving. No matter what they did to us, how they put us on this reservation, we’re still surviving.

Know oneself, and understand oneself.

From producers Aaron Henkin and Wendel Patrick, in collaboration with Arlo Iron Cloud and KILI Radio, voice of the Lakota Nation, it’s a special edition of Out of the Blocks right after this.

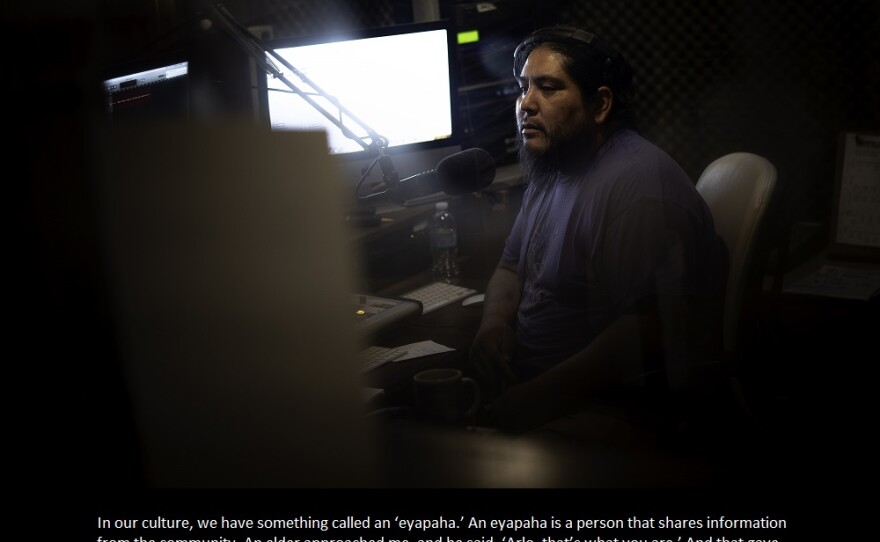

Arlo Iron Cloud: My name is Arlo Iron Cloud, and the last name—Iron Cloud—is a paternal name that has come through for many generations. I can go six generations back onto a man who was the origin of all the Iron Clouds. If we take his name, we can go up to the Battle of Little Bighorn, we can go to pre-United States stories, you know? So, like, my name is longer than the United States of America. We’re here at KILI Radio, Porcupine, South Dakota. At the radio station, we have a wind turbine that generates six kilowatts of power and on our building we have solar panels that generate five kilowatts of power, and just below the hill over here we have solar panels that generate twenty kilowatts of power, which probably makes us the greenest Indian-operated FM radio station out there.

Aaron Henkin: It is windy out here. Talk about this hill and just sort of how high up you are and just the amazing view that you have from this spot.

AIC: So, we’re at Porcupine Butte, the highest point on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Our radio tower definitely makes it the highest point. That’s a three-hundred-and-fifty-foot radio tower, and so we kick out about a hundred thousand watts of FM power and you can hear us in three states. Wyoming, Nebraska, and South Dakota. In our culture, we have something called an Eyapaha. An Eyapaha is a person that shares information from the community. I wasn’t really under the interpretation that I was an Eyapaha at first, but an elder approached me and he said that, “Arlo, that’s what you are,” and so that’s what I took that upon. You know, and it gave me a sense of competence within my own tribe and that allowed me to understand my role. If any American across the United States wants to Google what an Indian is, chances are a lot of Lakota people are going to pop up. We’re very known for our defiance and that has made us the poster child for the American Indian, and when America wants to remember the American Indian they go to the poster child and those media outlets come in here and they have their own agenda. And when I got a call from you, you sounded like me. You sounded exactly like me with the intention that you want to bond the people in your own community. That’s what you do in Baltimore, Maryland and I love that fact that you go to communities and you interview so-and-so, Joe Schmoe, and give him an opportunity to talk about who he is, why he’s a part of that block, and when it comes to belonging to anything, if you can just give that person that amount of time to know that they’re important, that they belong to something bigger, you solidify that block. And so, that’s the connection point. I mean, that’s what this radio station is, that’s what the Out of the Blocks podcast is, that’s what a lot of radio people do is that we’re connectors.

AH: So, a couple of words of transparency about our process, here… You know, Out of the Blocks, we spend most of our time in Baltimore, but we’ve started to travel around and we got in touch with you and we’re co-producing this episode with you, Arlo, and we’re entrusting you to introduce us to a cross-section of folks across the reservation. Talk to me about the voices that you’re gonna introduce us to during this time we have together and what you hope that we’re able to take away from the experience.

AIC: I guess what I want to do is I want you guys to meet everybody that makes up Oglala Lakota in this part of the country. I want you to meet women’s rights activists, American Indian Movement members, students, teachers. I want those people that aren’t always heard to be heard. And I’d even introduce you to people I don’t like for the reason that… I need you to understand that this is bigger than me. That’s why I put you in their path.

AH: I just want to say I’m really grateful to have you as a partner on this project and that you’re putting your trust in us and in this collaboration. I think it’s going to be fascinating for folks who get a chance to hear it. I’ll say to you, “Pilamaya lo.”

AIC: Washte.

AH: I’m still learning. (both laugh)

Derrick Janis: Be safe, be cool, buckle up, and if you’re driving down the road, make sure you’re tuned in to KILI Radio, 90.1 on your FM dial. How are you guys doing? My name’s Derrick Janis, KILI Radio production manager. Weather-wise from this guy’s weather eyes it’s looking rainy. People are calling us all the time. Tomorrow the Grey Eagle Society, they will be having a meeting. So, it’s like the phones will ring and it could be something as random as, “Hey, we’re having a fry bread and [] sale over here and you know, write those down. Also, this one here is from the Wakpamni district says, “KILI, please announce…” Become a secretary along with all the other things you’ve got to do here. I can get back into some more jams out there, got some Native content for you… Myself, personally, I was fresh out of high school probably and my mom, she had a late show up here and it was like a 10-2 show and she was kind of, you know, “I don’t want to be at KILI Radio alone, so would you come with me?” So, I said, “Okay,” and we came up here, I drove her to KILI and she got quite busy answering the phones and dealing with people… You know, the nighttime scene of KILI Radio. So, I happened to catch her dead air and just went in there and start playing songs and talked on the radio a couple of times and that started it all off. I mean, my almost 17-year run with KILI Radio, and it kind of kept me out of trouble, being a young man, because here on the reservation, life ain’t all bananas and apples, you know? There’s some… there’s a few raisins in there and they want you to raise some hell and it’s the choices you make. So, I was making bad choices in my life before then, running with gangs and whatnot, so KILI’s kind of my savior. …And keep it right here on 90.1. My name is Derrick Janis. You got the coolest guy around until we are all done today. 2-6 is the early afternoon music mix, so that’s pretty much where it’s all up to the DJ. Maybe he likes to play hip hop, maybe he’s a country and rock person, so it’s good when they mix it all up. Myself, when I’m on the radio, I like to take requests and things like that because we’re constantly looking for new sounds and it’s right here on our reservation. You know, we have music-makers, we have poetry-tellers, and we have rappers, we have country… and it’s good to be that platform to just put them on the radio and say, “Any given day, if they come up here and wanna play a song for KILI Radio,” then it’s like, “Well, hey, let me clear my schedule for you and let’s see what you’ve got,” and it becomes the community’s station and then that’s what I mostly enjoy about being here at KILI Radio.

AH: Who do you want to turn me on to and put on my radar in terms of like, local young artists who are out here on the reservation?

DJ: You know, in my understanding there’s quite a few. Derrick [?], he goes by “Slim.” “Slim Main,” and he’s been doing his thing for quite some time now and, you know, he puts a lot of effort and energy and time into making his thing, so he’s kind of getting real good.

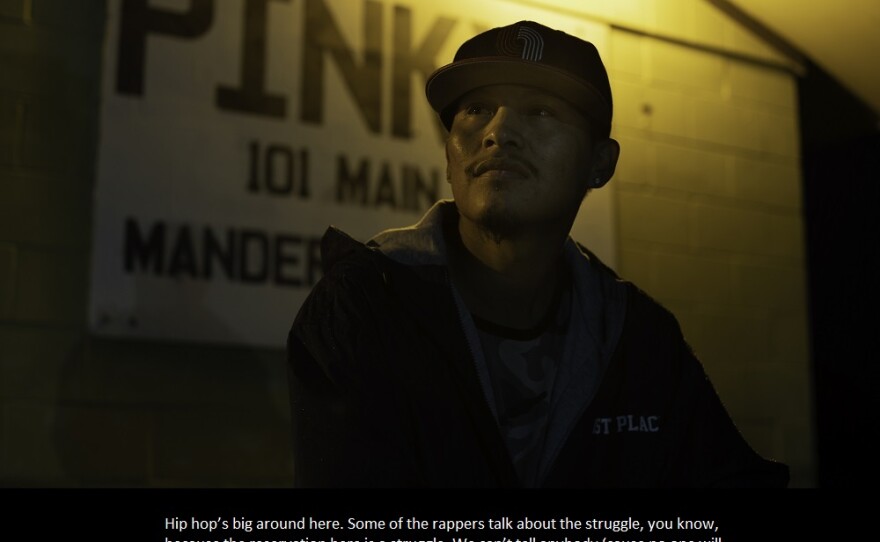

Derrick Looks Twice: I think hip hop will speak to anybody who listens to it. My name is Derrick Looks Twice. I’m from Anderson, South Dakota, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. You know, hip hop’s big around here. I mean, it’s like some of the rappers you hear from on the reservation, they talk about the struggle, you know? ‘Cause the reservation here is a struggle. I mean, we can’t tell anybody, I mean, because no one will listen, so we put it in a song and play it and, you know, everybody’s there listening to it and it just floats. Most of my songs are inspiration songs because I grew up a hard life, you know? Single mother, you know, dad not around. I mean, in town—this small town—he’s around in the small town but no acknowledgement from him so… I sit there, I write on tablets. You know, I’d have like, five different tablets where I’d just write and write and write. It made me feel like I could let anything out. Like, if I was stressed and if I had an anxiety attack, I’d sit there and write about it, you know, and it’ll release. The mainstream artist, the one rapper I kind of related to and, you know, I loved his music so much, I still love it today, it was Eminem. Slim Shady, yeah. I related to his music a lot. I mean, you know, growing up, single mother, you know, dad not around, I mean… Eminem, Eminem was like one of the main…main I listened to. I listened to his music every day.

Wendel Patrick: You heard his new album?

DL: Um, not yet. I mean, I haven’t really got the chance to listen to it because I’ve been, you know, busy with some spiritual stuff, you know, because a couple weeks ago I overcame a drug habit. You know, so I turned to spiritual ways, traditional ways to keep me calm and, you know, since this day, you know, I never felt any happier, you know, about life, you know? Everything’s okay, you know? You know, what inspired me about the spiritual ways was my little sister. Her name is Summer Looks Twice. You know, she’s my best friend, you know? I was dealing with being a cocaine user, and four weeks, you know, I told myself, you know, “It’s… You need to quit the drug or lose everything.” So, I talked to my sister and we did a ceremony, where we did prayers with the medicine man. Every day after that ceremony it was like I got happier. I got more inspiration to go out and do things, you know, and I’ve been clean four and a half weeks now and I can say that it feels good, you know? I mean, I wish I never fell down that road, but I try to do better for my kids. I love my kids. I want to be a good father to my kids.

Jerome LeBeaux: Usually, a lot of our medicine men, they don’t start until they’re older in life—forties, fifties—but it was our elders that asked of me at a young age to start young. So, I was a twenty-year-old medicine man, you know? And that was a challenge in itself. My name is Jerome—Jerome LeBeaux. My mother is Tess Pourier LeBeaux. My father is Lyle Dusty LeBeaux. They were told when I was still in the womb of my mother that I was going to be doing this. So, I was real fortunate in growing up in different medicine men taking time to come see me and tell me, “Hey, this is what’s coming. This is what you need to prepare for.” And there was a time where I was resistant because in high school, I was playing basketball. I was a first team all-state, so I was at a crossroads because it was the time of when I was going to be beginning my role as medicine man per se and then I had the opportunity to go on to college and play. But I was advised by my elders to stay back because this was my true role, and it wasn’t an easy decision. It was hard because I guess the selfish part in me wanted to go on to play basketball, but I guess what sped that decision along, too, was that I tore my ACL and MCL, too. So, that helped my decisions in staying home to begin as a young medicine man. So, I started at twenty years old and I’m forty now. I’m a young forty, but it seems like I’ve seen a lot, did a lot, lost a lot, gained a lot. So, I guess it’s made me stronger, too, because there’s people out there having it harder. This land down here that Thunder Valley’s on, it was a sun dance circle and it still is. It’s one of our cherished ceremonies because in this ceremony, for four days we go without food and water, and we dance in the sun for four days straight. We’re giving back. It’s a renewal process and I have heard some people say—because there’s young people, you know, in their late teens—that do this too almost like a rite of passage. But the social needs that our people… we would notice, we would dance, it would be beautiful, we would hear people say, “I’m scared to go home. I’m scared to go back to what’s out there,” because those same social problems existed. So, we thought—as spiritual leaders, my friends who help me—we sat back and thought, “What could we do more? What could we do more to help our people?” And we decided to start this non-profit, you know, and we had wild ideas of what we wanted to do, and some of those… I guess we weren’t afraid to dream. We weren’t afraid to dream, and I look out here… I see a vast amount of people… and that’s been something that we were able to open this door and collaborate and work with all types of people to make Thunder Valley what it is, you know? And it’s been a beautiful thing… It’s been a beautiful journey.

Andrew Iron Shell: When I started here in 2012, this was an alfalfa field. There was just one red building here and we had a lot of hay growing out back here and now we actually have a community growing here. This is Andrew Cat Iron Shell. I am the community engagement coordination for Thunder Valley CDC. We’re standing here at the Thunder Valley Regenerative Community Development, which is located—geographically—about center on the Oglala Lakota Nation here in South Dakota. Right in front of us, we have a demonstration farm, which is 2.5 acres. It has an organic garden. We also have a chicken coop with about five hundred chickens in there, which is part of our food sovereignty initiative. And beyond the farm here, we have 21 single family homes going up, some in construction and some are actually occupied now within the last couple months by families. So, they have closed on their home loans and moved in. For right now, we can see seven completed homes in a cul-de-sac that is set up into halves… horseshoe-type setting, and that’s traditionally the hierarchy of how we used to camp, so it’s very culturally appropriate. It doesn’t have your parallel streets like your average American apple-pie community. So, it really is a reflection of what a Lakota community should look like in 2018.

AH: People are probably surprised to learn—who aren’t from here—just what a housing shortage there is on the reservation. Just the number of families and the number of houses just don’t match up.

AIS: Exactly. The current need today as we stand here is 4,000 homes that are needed. So, it is homelessness, but it looks different on an Indian reservation. You don’t see us laying out on the street, on the curb with no support system. We actually—whether we have the resources or not—ask family members to stay with us. So, you might have two, three, even four families living in a one, two, or maybe three-bedroom housing situation. So, that affects a lot of the social ails that we experience in our community. It’s related to over-crowded housing.

SL: We’re installing solar panels on top of the roofs and we’re hooking them up to the houses. My name is Severt Long Soldier. I am Oglala Lakota and I’m a solar intern.

AIS: One of the main things we have is a work force program. So, we have young people, working on their GEDs or early college classes. They are also learning green construction.

SL: I wish to graduate with a bachelor’s in public health, biology, and calculus.

AIS: We’re also wrapping them around different services for them. So, they take financial literacy, we help them to be banked so they start a savings account, so they learn how to save money, and potentially, they could go on to the employee-owned construction company, which is also working back here.

SL: Our reservations… I hope, like, one day there’s a day where there’s no more trailers. There’s just these houses or even better houses, with everybody living in them. No more homeless people or anything like that. I see a bright future ahead of us and Thunder Valley’s leading the way.

AH: Listeners will be able to hear your feet going through some seriously squishy mud. As we’ve been walking around, it’s been pretty soggy out here.

AIS: You bet. So, October is kind of the transition out here on the northern plains from maybe 120-degree summer to… eventually, we’ll get to literally 20 below zero here.

AH: And these houses are good to go in all those different temperatures?

AIS: They are. They’ve been well-designed and it’s actually the first time in this tribal nation community where families and community got to pick and choose what type of housing opportunity we wanted. Typically, historically, it’s just been a cookie-cutter opportunity from HUD that maybe designed houses for the south, maybe for Florida, Louisiana… somewhere down that way. But cookie-cutter did not work up here in the northern plains where they were inadequate for the climate that’s here and the extremes we have. And again, everything here does have solar on top, so we are working towards our renewable energy goals and our intention is that at the end of the day, all the energy we use in these 34 acres will be created in these 34 acres. It’s really about meeting a prayer half way. You know, we could wait forever for Uncle Sam to honor their legal obligations but we’d still be waiting, just like my father waited and his grandfather waited and they’ve been waiting forever. This is a way to kind of hold Uncle Sam’s feet to the fire, and say, “You gotta meet us half way, because now we’ve got a real family and a real housing opportunity.” So, how do we make the dots meet and the stars align for families living out here to meet these opportunities, and so it’s about empowering community people to do this, versus monopolies or corporations or tribal or state government. When people actually put their minds to it, they can do anything. So, I think that’s what I’ve learned by just being a part of watching this community develop in the way that it has.

Multiple Voices: From the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, it’s one neighborhood, everybody’s story. Out of the Blocks.

Theresa Two Bulls: My Lakota name, when you translate it in English, it’s “First to Stand with the Feather.” Eagle is very sacred to us. So, in our culture, the men hold the eagle feather. But I was given this name—First to Stand with the Feather—because of the path I’m walking in. My name is Theresa Two Bulls. I’ve been in politics since 1988, I’d say. Got elected as a tribal secretary and then I ran for vice president. Vice president and president positions were always held by men, so I ran. When I ran, I lost by 150 votes. But that didn’t stop me. I tried again and that’s when I got in. I got more votes than the two candidates that ran for president. So, that showed me that women can hold men’s positions. I was told by an elderly that our society is male-dominant and you’re going to have a hard time, and I explained to him that I didn’t want to say women are better than men. I want us to work together to balance out how we’re going to work for our people and how we’re going to make sure their future is intact. We really never had a good relationship with the state of South Dakota. One governor at one point would tell the tourists not to come on the reservation because they were gonna get robbed, they were gonna get beat up… and so that would keep the tourist money with the state instead of… You know, we’re part of the state, we should all work together. And so, when I got in as state senator, I think that I opened their eyes to the Native American tribes of South Dakota and that we are just like them. We have needs too and we can work together.

AH: You were the first female Native American representative in the state senate in South Dakota. Then, you became president of the tribal council here at Pine Ridge. Then, you took a break from politics.

TTB: Yes. That break was necessary because my husband got leukemia. You know, when he passed away, I went into depression… You know, I more or less just stayed to myself. And it’s been five years and I’m still grieving, but not as much so, and realizing that when people approach me to run this time it was for a reason. The people needed me.

AH: Say a little bit more about that. You… People started clambering for you to get back into politics. Tell me what’s gone into that decision and why you feel like you need to do it.

TTB: Our tribal government isn’t helping us. Suicide, drug and alcohol abuse… A lot of this is within our nation now and how do we address it? Tribal government is not trying to address it, and I love the people and I would do anything to help them. So, it’s hard here on the reservation. It’s not like on the outside world. But we can help ourselves and we can help each other. And seeing all this beautiful scenery—all the trees and the rolling hills and the flat part of it—it’s ours. It’s ours, you know? It’s always been ours. If you look up the research on it, 1851 and 1868 treaties, you’ll see how large our land base was until the federal government slowly dwindled it down to where we’re on this reservation that’s about fifty by a hundred miles. But yet, we’re surviving. No matter what they did to us, how they put us on this reservation, we’re still surviving.

Steven Yellowhawk: Saturday’s always our biggest day, so we expect to have about a thousand dancers out there. I think we have close to twenty drum groups that are set up here.

AH: And you’re the organizational mastermind behind all of it?

SYH: (laughs) Uh, I’m the scapegoat. My name is Steven Yellow Hawk and I’m currently the board president of the Black Hills Powwow Association. We are in our second day of a three-day event, the Black Hills Powwow, here in Rapid City, South Dakota and the contest is already underway. All of the dancers and singers are here, competing for over a hundred thousand dollars in prize money, all the way from the young, tiny tots all the way to the platinum age categories. But yeah, altogether, I mean there’s so many volunteers, so many people that are behind the scenes that you don’t really hear about that much, but they really help us make this event possible, sponsoring prize money from local businesses, the school district here in Rapid City… Just everyone really comes together as a community of one to make this powwow possible every year. So, I wasn’t really involved in my culture until I was about a sophomore in high school, and that’s when I really got into wanting to learn about the culture. I told my grandpa at that age—I think I was about fourteen years old—I said, “Grandpa, I want to dance. I want to put on those beads and those feathers and I want to dance to that drum.” He made my first regalia for me and this actually, this powwow here in Rapid City, 21 years ago, was the first powwow that I ever danced at as a traditional dancer. I actually still remember the car ride to the civic center here. I remember feeling very nervous and my grandfather… He apologized to me because he said, “I’m sorry I never learned how to dance as a young man or a young boy.” But he was going to point out an individual to me here that I could follow, I could watch, observe, to learn what it is to be a traditional dancer. So, we arrived here to the main room. I remember him helping me put on my regalia, and then he points out that individual and he said, “I want you to watch this man, how he treats the children, how respectful he is to elders, how he expresses himself while he’s dancing on that arena floor.” And so, since that point, my grandfather actually started dancing one year after I did at 62 years old and he tells us he feels more alive than he’s ever felt in his life. He grew his hair long, and you can just see it in his spirit, you know, kind of coming out of that shell. For so long, the church told him that the culture was evil and that he shouldn’t partake in it, so he wasn’t speaking his language, he wasn’t dancing, for sure. But now, to see that washed away and… It was a very unfortunate time that he had to go through, but now it’s awesome because he’s teaching us to live it, to use it, and to share it.

Joe Pulliam: My name is Joe Pulliam. My Lakota name means “the Warrior in Front.” I’m an artist from Oglala Lakota Nation, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Prisoner of War camp #334. I don’t acknowledge the state of South Dakota because it’s illegal. About ten years ago I started getting into the fine arts and started learning about ledger art. The history of ledger art originated early reservation time-period where our tribal artists, you know, were limited to art materials and there was a lot of ledger books, you know, accounting books from government agencies, trading posts, things on the reservation. So, you know, a lot of them were commissioned by military officers to do drawings on these ledgers, so a lot of them preserved their own histories and tribal histories. And so, that’s where I am now, using my own process.

AH: These ledgers… they’re sort of administrative sheets of paper that have been used and kind of cast aside by whoever was “running” the reservation, and then the Native Americans on the reservation would get them into their hands and use them as canvases for their own work.

JP: Absolutely, yep. All of these lines and these letters and these numbers… and they all represent economy and numbers... And to me, I’m really kind of reclaiming that paper and saying, “This is what Lakota culture represents.”

AH: And the medium… it’s like watercolor, real thin paints so you can see the image that you’ve put on there, but behind it is the ghost image of that economic document that it’s been painted on.

JP: Right. I draw the image right on the paper and then I just paint it with the watercolor, and it does allow for a transparent coat of paint and lets the original letters and numbers come through in the art, and it really becomes a part of the artwork, of the statement that it’s making.

AH: Just paint a picture with words as you have with watercolors about what we’re looking at.

JP: Right here, I painted on a ledger from Pennington County, South Dakota, dated 1899. This county was established on stolen Indian treaty land. Just this year, Pennington County awarded a mining company the use of a million gallons of water from Rapid Creek, which is a very sacred creek our people’s water source. So, when they did that, it really violated not only our treaty but it violated grandmother Earth, and so I did this piece to kind of protest that and it’s called “Water protectors’ camp on Rapid Creek.” So, you know, you’ve got the black hills in the background and you’ve got the water in the front and the foreground here, with the reflection of the moon in the water.

AH: Yeah, you get the blues and golds in there, and it’s all in the background done over a canvas that’s this official South Dakota document.

JP: Right. Historic document right there. And so, from a perspective of an Oglala male, seeing my people suffer for decades now and not anything being done, I realize it’s time for us to step up. I’ve learned a lot and I’ve been giving back to the people, my people, and one of the things I’ve done is to help organize the Lakota Oyate Artisans. What we really represent is a group of people empowering ourselves with art and with our culture that we can share with people, and you know, really bring some sort of economic development on a reservation that’s just been forgotten and that’s never been meant to succeed or develop. So, we’re gonna do it ourselves.

Corey YellowBoy: This is all Yellow Boy land here. This is my aunt that lives across the highway. All that land to the back there, that’s all our land, so… And I have all my family that lives just on the other side and down along the creek, and we have… my uncle has all his horses up here. My name is Corey Yellow Boy. It’s an old Oglala name, and around here on the reservation you can usually tell where somebody’s from by their last name.

AH: You have an adorable puppy.

CYB: Yeah. That’s Jake. That’s about his third or fourth name now because he wouldn’t answer to anything else I called him, so… But Jake… he’s been a good dog. He’s been… He keeps me company and he’s learning Lakota as well, he’s starting to understand Lakota, so…

AH: Tell me about your home here.

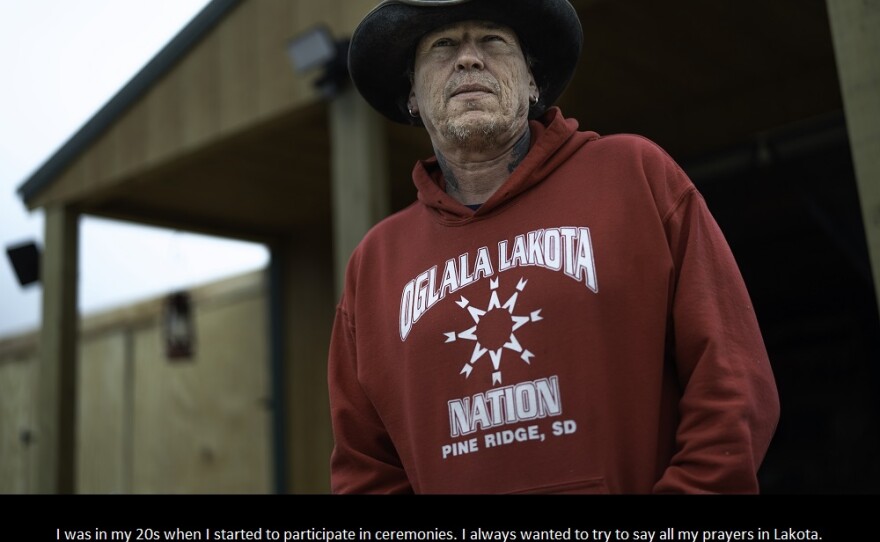

CYB: It’s not much. It’s just a little shed cabin and don’t have any electricity, don’t have any plumbing. I get my water from over at my cousin’s place and keep it over here in buckets and I have kerosene lamps and my wood stove, so... “Sloleechina a eecheeblazah” (phonetic spelling)… It means means, 'to know oneself, and to understand oneself.' Growing up, a lot of my cousins and myself, we weren’t taught the language, we didn’t speak the language, and I think I was in my…probably twenties when I started to participate in ceremonies and at that time, there were still a lot of Lakota speakers around. So, I always wanted to try to say all my prayers in Lakota. That was the first thing; I wanted to pray in Lakota. And at that time, in the nineties, there wasn’t a real big excitement or push to learn the language. Like, now there’s been a kind of revitalization of the language. You see a lot of people—and especially younger people—really coming back to the language and pushing themselves, but back in the nineties it was tough. I mean, there wasn’t really any materials to learn from, and so if you wanted to learn you had to actually go and talk to people, and I think that was probably some of the best training—I guess—in the language because you not only learn the words, but you heard stories about the language, you kind of got the background of the culture.

AH: If you think about your own life as a story, what do you think the moral of your story is?

CYB: Well… Well, this I guess…it’s the story of the Chinese farmer. I’m sure you’ve probably heard it. There’s this Chinese farmer and he wakes up one morning and his horse ran away, and so all the people in the village, they come up and they say, “Oh, that’s too bad,” and he just kind of stands there and he says, “Maybe.” And the next day, the horse returns and he brings seven other wild horses, and all the people in the village come up and they say, “Oh, that’s great!” and he just stands there and says, “Maybe.” The next day, his son goes out and he tries to break one of those wild horses and he ends up getting thrown and breaks leg, and all the people in the village come up and they say, “Oh, that’s too bad,” and he just stands there and he says, “Maybe.” Then, the next day some of the people in the army come around looking for young men to conscription into the army and they pass on his son because he has a broken leg, and so all the people come up and say, “Oh, that’s great,” and he says, “Maybe.” And so, the whole meaning of that is you can never tell the outcome of something positive. You can never tell if it’s going to be good or bad. You can never tell what is the outcome of something bad that happens. Like, to me, that’s life. I mean, that’s my life because yeah, I’ve had ups and down, but from some of my downs I’ve met other people, I’ve had new experiences, you know, and from some of the things that I thought brought me joy, then, you know, it was the opposite. And I think that’s kind of sums up the reservation, too. I think a lot of Lakota people, we take the hard times because we always know that something good can come of it, and even when it’s something happy, like, we’re always thinking, you know, something down the road could happen. And so, I mean, it’s just life. You just have to live it.

Multiple Voices: You’ve been listening to a special addition of Out of the Blocks, produced by Aaron Henkin and Wendel Patrick, in collaboration with KILI Radio, voice of the Lakota Nation. Special thanks to Arlo Iron Cloud of KILI Radio and WYPR’s Katie Marquette. Aaron and Wendel want to thank all of us who took a deep leap of faith and shared our stories and our lives. From WYPR and PRX, this is the Pine Ridge Reservation signing off.

AH: Is there a word for “goodbye?” Somebody was telling me there might not be a word for “goodbye.”

There’s not word for “goodbye.” We just say, ‘Toksa Akhe,’ which means, “See you later.”

This episode was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Out of the Blocks is also supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Cohen Opportunity Fund, The Hoffberger Foundation, Patricia and Mark Joseph, Shelter Foundation, Inc, The Kenneth S Battye Charitable Trust, The Sana and Andy Brooks Family Fund, The Muse Web Foundation, and the William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund, creator of the Baker Artist Portfolios.