The Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project

The controversial Maryland Piedmont Reliability Project (MPRP) would cut a 150-foot-wide line across 1,200 acres of farmland in Baltimore, Carrol and Frederick Counties. To do so, it will have to encroach on the private property of hundreds of landowners, who worry about what the project would do to their land.

The developer, Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), submitted the MPRP’s application in December of 2024. It said the goal was to strengthen Maryland's power grid, but opponents argue it's an extension cable for Northern Virginia data centers. PSEG’s application was ruled incomplete by the Department of Natural Resources’ Power Plant Research Program, which said it lacked reasoning as to why alternative routes were rejected, and data on the power line’s environmental impact.

As that played out, PSEG took more than 100 land owners along the route of the MPRP to court for access to their properties this past April to survey them for the project. It won the case, and now must provide 24-hour notice before entering someone’s land. But it retains access until the Public Service Commission (PSC) rules for or against the MPRP.

StopMPRP, a grassroots non-profit opposed to the power line, filed an appeal shortly after the decision was announced. On July 15, PSEG filed an additional lawsuit, naming 200 more landowners.

Brandon Hill’s Food Forest

Brandon Hill, a farmer in White Hall in Baltimore County, started his food forest four years ago with the purchase of 60 acres of cropland, old growth trees and wetlands.

Food forests are an alternative to modern farming, replacing neat rows of corn and wheat with an entire ecosystem of flora, fungi and fauna.

He lives right next door to his family home, and says this is his, “American dream.”

“I worked very hard,” Hill said. “I got to start this passion project, this conservation farm and I was lucky to be able to do it so close to my family.”

Today, Hill tends to 15 blight resistant hybrid American Chestnut Trees, harvests honey from his bee hives, and has identified close to 30 varieties of mushroom growing on his land.

Trees don’t grow in a day, and Hill knows this could be a 30 year long project. Hill plans to expand to a second field on his property and hopes to one day hold educational courses for children on nature and the environment.

In April, Hill was listed on a lawsuit PSEG filed to gain access to the properties of more than 100 landowners along the route of the MPRP. The provider needs to perform land surveys to gather data on the environmental impact of the project.

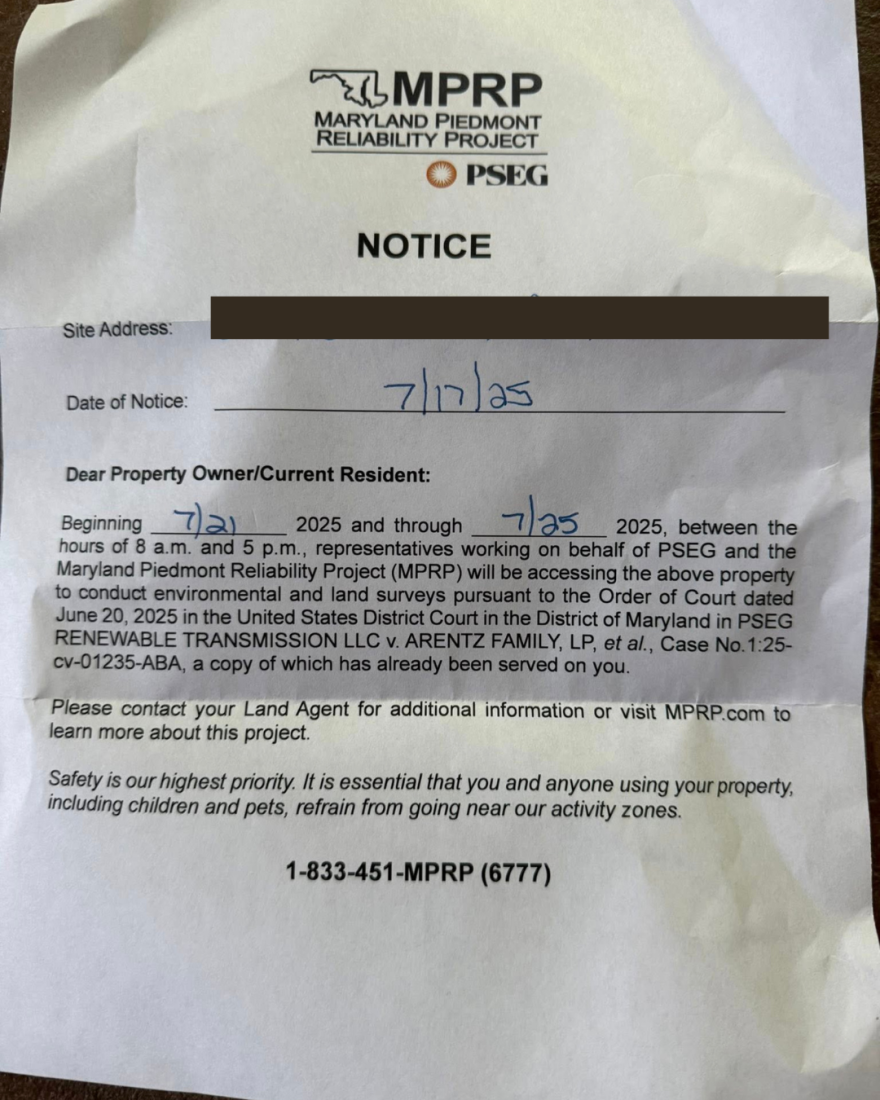

Hill was woken by his wife on July 17th as a group of PSEG representatives walked up his drive way to tape a paper note to his door. Hill lives in a secluded area at the end of a long drive way and says he’s never had someone come directly to his door. “[We live] down in a valley, it’s not easily accessible,” Hill explained. “It was unnerving and very unexpected.”

PSEG had just served Hill with a notice they would be coming onto his property in 24-hours, a requirement of the lawsuit.

The letter instructed Hill and anyone else on his land to stay out of the zone PSEG would be operating in. Hill works on the land, and is concerned PSEG is already trying to tell him how to use his property. “If they’re already trying to tell landowners where exactly they’re allowed to be on their own property, just think about once the line is under construction,” Hill said.

If the MPRP is approved and PSEG builds across Hill’s second field, the farmer says he’s worried the entire portion of his land will become unusable. “This will be really hard, personally, for me to recover from, if they destroy this piece of land here,” Hill explained. “I have grown up here my entire life and it does mean so much to me, and it is my American dream.”

River Valley Ranch

River Valley Ranch (RVR) is a faith-based non-profit youth camp located in Manchester, Carroll County. It sees more than 10,000 children and adults on their campus each year.

Jon Bisset, RVR's Executive Director and President of Peter & John Ministries, says they use their camp’s 500 acres to give kids a way to escape modern technology. “What is central to camp is getting kids unplugged and out of the cities and into the unspoiled nature,” Bisset said.

The camp was founded in 1952 by John Bisset’s grandfather and his brother, who traveled from Scotland and became pastors in Baltimore City. The brothers opened the western style, “dude ranch,” after seeing so many kids without anything to do in the summer.

RVR is one of the properties listed on the PSEG lawsuit, though they had not been notified PSEG would be coming onto their property yet.

The camp reached out to negotiate a time for PSEG to come onto their property in the fall as RVR is in the middle of its summer season. Bisset explained PSEG’s presence would raise serious concerns for camper safety. “The idea of posting a note on our door…and just coming on our property and wandering wherever they want unsupervised, unbackground checked, is not a solution that works for us,” Bisset explained.

All the staff at RVR are vetted before being allowed on campus and Bisset says PSEG will be no exception. RVR expects PSEG to comply with all the safety protocols the camp has for its own workers. “We’re not going to let them walk around unsupervised, so we have to pull someone off of another job in order to make sure that happens,” Bisset said.

The MPRP may interrupt more than the summer season. There are plans to move the camp out of the flood plain it currently sits in, and away from a road that cuts through the camp. Bisset says those plans may not be an option if the MPRP cuts their land in half. “If we are unable to relocate this property, which we need to do, we will lose out on what we need to stay in business,” Bisset explained. “If we’re not able to use that land for camp in the future, it will have a significant financial impact.”

The route the MPRP would take cuts across the part of their land they want to move to. Bisset says he’s worried parents won’t want to bring their kids to RVR with the power lines overhead.

The Moran Family Home

Frank Moran bought his land in Adamstown, Frederick County, in 1979 after searching for a secluded place where he could live off the grid.

Since then, he and his sons have built three homes on the property.

Two generations of the Moran family forage and harvest resources from the land they’ve built their lives on, gathering several meals worth of food every week. They draw their water from an underground aquifer and chop wood to heat their homes.

When PSEG filed a second lawsuit earlier this month, this time naming an additional 200 properties along the route of the MPRP, the Moran family found their name was included.

Moran hasn’t seen his day in court yet, but hopes StopMPRP’s appeal of the first lawsuit may come into play. His son, Matt Moran, says PSEG’s presence would disrupt their daily lives. “To give us 24-hour notice and then after that point, be allowed to come at their will, is extremely intrusive,” Matt explained.

That intrusion may extend to the Moran families drinking water, as the MPRP could be built over top of the source of their well. Mat is concerned how run off could affect the stream that bubbled up from the ground and flowed into larger rivers.

Frank wasn’t just worried for his own family, but for the safety of the surveyors. He pointed to their logging efforts, explaining the dangers of felled trees. “You could wind up getting stuck out here if you came out when we didn’t know you were here and dropped several logs along the trail,” Frank said.

Surveyors would also have to look out for “widowmakers,” as Matt called them, or dead trees that were still being held up by their neighbors.

If the MPRP is approved, Matt doesn't intend to allow PSEG to go about their business unsupervised. He plans to document the work they do on his land and says he’s already put down game cameras where he thinks they will work. “I don’t trust these people as far as I can throw them,” Matt said.

Matt Moran says he’s concerned for the environmental impacts the MPRP may have on his property, and more broadly across Maryland.

The PSC announced in June that it would not schedule any further hearings on the MPRP until PSEG was able to provide information missing from the MPRP’s application. Namely, the environmental impact of the power line, and reasons why alternative routes were rejected.