An Anne Arundel County home’s ties to enslavement can be found beneath its soil and in the historic record.

But descendants of those enslaved believe their history is threatened.

When you enter the Belvoir Manor house from the basement and climb the stairs to the first floor you encounter history.

Julie Schablitsky, the chief archaeologist for the Maryland Department of Transportation, said the original stone house was built by Francis Scott Key’s grandparents in 1736. Then a brick addition was built in the 1780s by the owner and enslaver, Dr. Upton Scott.

“He was kind of banned from Annapolis a bit because people thought he was a British sympathizer,” Schablitsky said. “And so he was here living away from his Annapolis home and in doing that I think he was building, and then I also think that’s about the same time when a quarter for enslaved people was built too when they were firing all of these bricks up.”

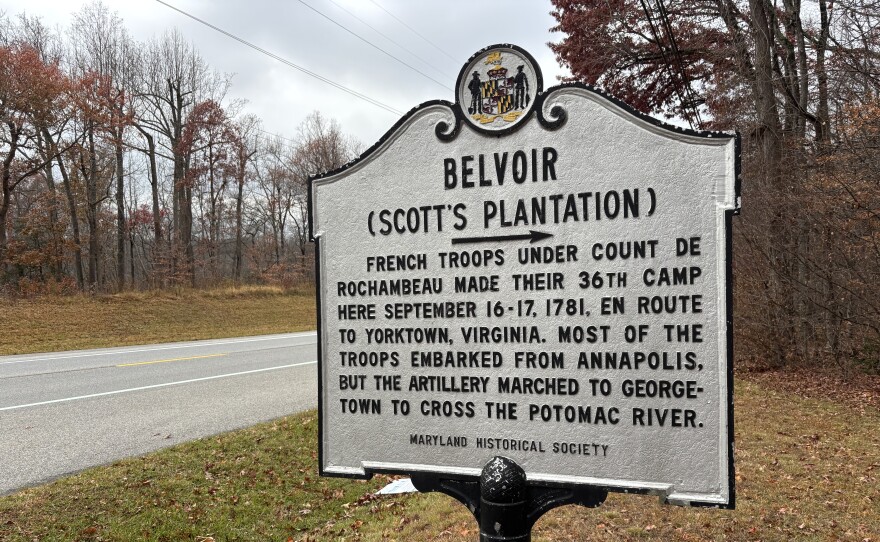

Schablitsy found evidence of the building where enslaved people once lived while looking to no avail for something else at Belvoir. The French commander Comte de Rochambeau and his 4,500 troops camped there on their way to Yorktown in 1781.

“And instead of finding France we ended up finding Africa,” Schablitsky said.

A short walk from the home is a 32 by 32 foot site that was loaded with evidence and artifacts like stone walls and a brick floor, pieces of ceramic, and what Schablitsy calls the smoking pipe, a clay pipe with DNA that proved its user was a woman of African ancestry.

Wanda Watts has her fourth great grandmother’s manumission papers which prove she was enslaved at Belvoir.

“We know her husband, who was a free man, who was a glass maker in Annapolis and Baltimore, he purchased her and her daughter from here,” Watts said.

Pam and Larry Brogden, who are cousins, believe their family was at Belvoir too. There was a woman, Cinderella Brogden, who was enslaved there in the 19th century. Cinderella and her husband Abraham, a freedman, ran away to Baltimore but were captured.

“Abraham went to prison for three years,” Pam Brogden said. “They don’t know what happened to Cinderella.”

“Cinderella and Abraham, there’s a little gap between that and my great grandfather who came from slavery but we don’t know where,” said Larry Brogden.

On a recent tour of Belvoir the Brogdens, Watts and Schablitsky were taken aback by its condition.

“This is sad that we’re losing the main house,” Schablitsy said.

They had not been there for several years.

Watts said, “It’s really dilapidated and overgrown.”

Windows are broken. Fences are overrun by weeds. Watts said they have reached out to the owners.

“We’d like to see the manor preserved as well as the slave quarters and the area that we believe is the burial ground,” Watts said. “Preserved in some manner, not to disappear.”

Schablitsky said, “This is a very very significant site in Maryland and it is threatened. It is actually threatened. It’s not preserved. There’s nothing to keep it from being developed and lost forever.”

The property is owned by Luminis Health, which owns Anne Arundel Medical Center.

In a statement, Justin McLeod, Luminis’s media strategist, said Belvoir was donated to the company.

He said, “We appreciate its historical significance to its ancestors and our community. The Belvoir House remains in the same condition as when it was gifted to us, and we have engaged a professional property management company to maintain it.”

McLeod added there are no specific future plans for the property.

Gabby Reed, the director of communications for Anne Arundel County, said in a statement that the county has no plans to purchase the property.

On Nov. 22, Anne Arundel County Executive Steuart Pittman gave a formal apology for the government’s role in the institution of slavery and its lasting impact on the Black community.

Pittman said, “As County Executive, and as a direct descendant of Anne Arundel County enslavers, we collectively offer our inadequate and long-delayed, but deeply felt apology, and pledge to never allow this history to be forgotten as we work together toward atonement.”

Schablitsky has written a book, Belvoir: An Archaeology of Maryland Slavery. She offers clues on how the enslaved lived their lives.

Larry Brogden said growing up, he mostly heard about the enslaved in the south.

“History said there was some slavery somewhere, but we never thought about it being here or anywhere this close to us,” Brogden said. “A little knowledge, you’re never too old to learn a little something.”

Despite active local descendants and physical evidence of enslaved people, Belvoir’s historic marker on Generals Highway tells only about the plantation’s ties to Rochambeau.