An orchestra files onto stage. A crowd of onlookers watch virtually on YouTube as the first chair violinist walks out last, holding a large, memory foam plushy of a pixelated dog. The crowd goes wild when they see the derpy looking dog and they start spamming chat with emojis: The dog is, in fact, the conductor. Now that he's here, after hours of waiting, the concert can finally begin.

What is it all about? This orchestral event celebrates the five year anniversary of the video game Undertale; everyone in the audience is here to experience a game they love in a new way. It's a big celebration for a small game, made primarily by one person.

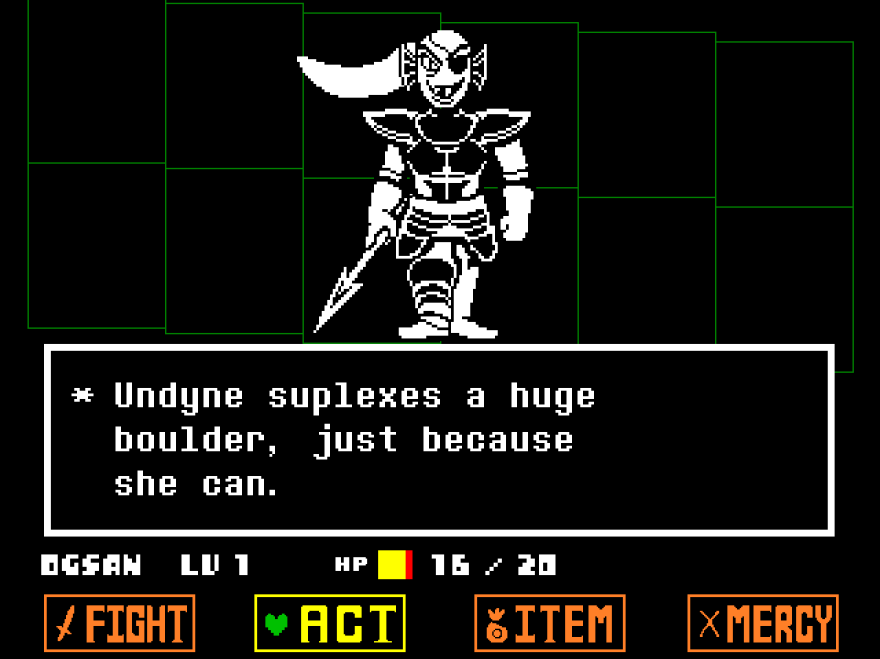

Undertale is a roleplaying game that puts you in the shoes of a child who falls into a pit of monsters. But unlike others in its genre, in Undertale you can fight those monsters, or resolve the encounters peacefully. Toby Fox, Undertale's lead developer, released it for Microsoft Windows and OS X in 2015. Since then, it's been published in Japan and ported to several different consoles.

"I was really happy to see all the responses to [the concert]. I was really surprised by how moved everyone was, despite the fact that it has been five years. Obviously time passes and you have nostalgia for something, but to me, It's interesting to see how relatively quickly that nostalgia appeared and how deep everyone's feelings are. It's really nice and really validating to see as a creator," Fox says.

Undertale's premise — that one can resolve violence through peaceful means — cut through the cacophony of commercial video game development predicated on violence and linear character progression. This, combined with the game's offbeat sense of humor and catchy soundtrack, made it an instant classic.

But Undertale didn't just sell millions of copies. It shaped the entertainment tastes of an entire generation. For its largely younger fanbase, Undertale took on a new life through memes.

"I really think that Undertale was a perfect storm when it came to impacting broader internet culture in a big way," says Palmer Haasch, digital culture reporter at Insider.

People are going to keep talking about 'Undertale,' and memeing 'Undertale,' because it's a great game, but also because it's so foundational to their internet experience as well

"It's got a fun, recognizable aesthetic, a chiptune-esque soundtrack that fits right in with TikTok's musical tastes, and a storied meme legacy that traces back to massive fandom engagement around its release."

"For a lot of zoomers (members of Gen Z) like myself, it's also something that's deeply nostalgic," Haasch adds. "This game came out while I was just starting college, and for many others, while they were in middle and high school. People are going to keep talking about Undertale, and memeing Undertale, because it's a great game, but also because it's so foundational to their internet experience as well."

MakingUndertale

The first time I played Undertale, I played it like every other game I had experienced up until that point. I fought the monsters. I beat them. I leveled up and got stronger. Then, just before I got to the end, the game slapped me with a dose of cold, hard reality.

A skeleton monster named Sans — named for his in-game font Comic Sans — explained to me what atrocities I had committed in order to reach that point. As it turns out, those so-called "monsters" I killed were creatures living their own rich lives. Some of them were beloved of other characters, and maintained upstanding reputations as community members.

I returned to the game determined to right my wrongs by starting a new save file. The second time I played through, I didn't kill a single monster, and Undertalerewarded me with catchy new battle themes, a longer story, and new characters.

Talking to other characters to help resolve conflict is central toUndertale. Designer Toby Fox says he was influenced by another game called Shin Megami Tensei.

"I liked that you could talk to monsters and defeat them in a pacifist way [in Shin Megami Tensei]. So I started designing a game system where you could beat most, or all monsters just by talking to them," he tells me in a video chat. "Once you do that, and you have to talk to the character, you have to interact with the character, in order to 'defeat' them, you end up having to put personality on every character and every character ends up becoming their own unique figure and then the game's story starts coming together."

This battle system informed how Fox wrote the story. "The story of how I wrote the game is also the story of how I developed the game since the system and the story are intertwined."

"Surprisingly it's the first full game that I wrote," he adds. "At the time, I didn't have a strategy. I just did things arbitrarily. Some of the story was almost written improvisationally at the last minute."

Originally the first boss of the game, Toriel, you had to kill her to progress the game. That was how the game was going to work. And then I was like, 'this sucks' and I changed it before I released the demo.

And for the first time, he shares a story about how Undertale could have been very different. "Originally the first boss of the game, Toriel, you had to kill her to progress the game. That was how the game was going to work. And then I was like, 'this sucks' and I changed it before I released the demo," he says.

Slowly, the game came together as Fox built it up character by character, battle by battle. "Really [Undertale] is just a huge katamari of things that I like that I combined arbitrarily."

The image of a huge katamari — a giant cluster of things (and another fabulously idiosyncratic game) — doesn't just feel like an appropriate way to describe Undertale. It's also a good way to understand the fandom that grew out of it. What started into a single game rolled up into a giant fandom consisting of all kinds of stuff: Millions of fans, fan video edits, fan art, cosplay, soundtrack remixes, and of course, a rip-roaring obsession with Sans the skeleton.

Five years down the line

Five years later, I wanted to take stock of the game's legacy and how it's present in today's culture.

"Undertale has gone on to become an absolutely dominating force," says Reid Young, CEO of Fangamer, the official merchandiser for Undertale, and the manager of the first ever Undertale fansite. "[Fangamer] ended up setting up a forum. It just instantly spiraled out of control. There was no way anyone could manage it."

Young had experience managing fansites for other games before — he founded Starmen, a site dedicated to a game called Earthbound-- but to him, the Undertale community is special.

"There are a lot of very talented, very emotionally intelligent people. They care very deeply about this game, but that also leads them to care about the people that they meet through the game," he says.

But despite Young's positive experience with fans, we should note that the Undertale fandom hasn't always had the best reputation. At one point, fans disagreed so passionately over the correct way to play the game that it led to toxicity online.

"You kind of run up against the rule of large numbers," Young says. "If you get enough people, you get the best and the worst. The barrier for entry [with] Starmen was high and that naturally filtered out a lot of people who could make trouble. The opposite was true of Undertale. So many people played it."

"The Undertale community isn't as bad as everyone says it is," counters a gamer named Marr. Marr, who prefers to go by her online name, moderates an online Undertale chatroom connected to the game's Reddit community.

"It used to have a bad reputation, but we moderate the server well and keep kids out, as well as the ones that are deliberately trying to disturb others."

The lessons of Undertale

Playing Undertale changed how I think about games. It made me think not just about all the characters I killed in Undertale, but every other game I had played before that. Why was killing the de facto way of making my way through so many worlds? There was always a part of me that felt like Pokémonwas low-key animal cruelty, but I managed to explain the discomfort away. Undertaleallowed me to sit in that discomfort and try to make a change.

Since its release in 2015, the game hasn't changed, but the lives of those who love it have. The 2016 election, the increasingly dire situation with the COVID-19 pandemic and the upcoming election are leading critics to think about the game in news ways.

Rebekah Valentine is one of the many game writers who spoke up about her love of Undertale during that orchestral performance. "I mean, of course, yes. It'd be easy to go into something about being kind to others or what love means," she says. "But I've actually been thinking of a line from the ending of that game lately."

Valentine pauses for a moment. "If you go back to visit a certain character right before finishing up [Undertale]'s 'happy' ending. He tells you to be careful in the outside world, that it's not as nice as the monster world and that not everything can be resolved by just being nice. Sometimes you have to fight."

Whereas Delta Rune, Fox's sequel to Undertale, is pretty explicit in its moral messaging that it's okay to fight back against a violent oppressor, Undertaleleaves more gray areas around when to fight and when to stubbornly insist on mercy.

"I thought it was a weird takeaway for the longest time, especially for a game that on its surface seems to push a very innocent view of empathy and goodness. But more and more these days, naïve as it sounds, I'm coming to understand the value of fighting back," Valentine says.

I think entertainment can be like mental medicine. People need things to give them hope, and sometimes that can be games.

And at a time when more and more people are fighting back, I asked Fox why it's important to make and write about games. (I myself had been struggling with spending all this time writing this article, when the police officer who killed George Floyd was released from prison, and people in my city were out on the street protesting.)

Fox seemed lost in thought — and then he said, "Sometimes it does feel really hard to be working on games and think like, 'What is the f*****g point of this when all of these horrible things are happening? Why am I working on games instead of out there fighting?'"

"I think entertainment can be like mental medicine," he continues. "People need things to give them hope, and sometimes that can be games. As long as you are not ignoring what's going on in the world so that you get to do games, it's good."

Ana Diaz is a freelance games writer and podcast host at MinnMax. She loves Pikachu and is based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She tweets at @Pokachee

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxODg3MTg0MDEyMTg2NTY3OTI5YTI3ZA004))