The moments inside a courtroom in Orlando in 2007 were quick and consequential for Marquis McKenzie. The 16-year-old stood handcuffed behind a lectern. A juvenile judge announced his charges, then apologized that he could no longer take up the case.

"You're being direct filed," he told McKenzie, who was accused of armed robbery over a cellphone and a wallet. "You understand what I'm saying? You're being charged as an adult now."

McKenzie remembers his mother wailing from the courtroom benches, begging the judge to reconsider.

"I had never been in that situation. I had gotten in trouble, but I had never gotten arrested," he recalls a decade later. "I just knew it was going to be a hell of a ride from there."

The juvenile judge's announcement meant that McKenzie was no longer solely subject to the rehabilitative services offered within Florida's juvenile system. He was now facing a 10-year sentence. A judge in one of the state's criminal courts would have the option of sending him two hours away to residential confinement at a youth facility, or to the juvenile section in one of Florida's medium security private prisons.

The latter is where McKenzie ended up. That same year, more than 3,600 other kids were direct filed and sent to adult court, too.

Across the country, lawmakers, juvenile justice advocates and community groups are shifting away from direct file, and rethinking their approach to handling kids and young adults who commit crimes. Florida, more than other states, has traditionally embraced an aggressive direct file system run by state attorneys who opt to transfer kids out of the juvenile court system and into the adult criminal system. The repercussions are great and the options for navigating the complex system are limited.

"Cruel wake-up call"

Florida was in the thick of its direct file culture when McKenzie's case was transferred to adult court. From 2006 to 2011, more than 15,600 youths passed through the adult criminal court system for violent and nonviolent offenses.

"That was a 'get tough' era in the United States," says Florida State University criminologist Carter Hay. "That was a time when there was a lot of concern about juvenile crime. There was a lot of media attention to the idea that there were these juvenile superpredators who were just a real threat to public safety."

Behind the trend were state attorneys, to whom Florida's direct file statute grants unfettered discretion to move any juvenile case to adult court without a judge's permission. The statute dates back to juvenile justice reform from the 1950s, when lawmakers were seeking to balance rehabilitation and punishment of youths who had committed heinous crimes. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, the direct file statute became the most used tool for handling children.

"A lot of these juveniles that have been through the system a lot, when they get arrested, their attitude is 'Nothing's going to happen to me. I'm a juvenile,' " says former 9th Circuit state attorney Jeff Ashton.

For more than 30 years he helped prosecute juvenile cases in Orange and Osceola counties, where McKenzie was direct filed. As state attorney, he spent four years having a final say over which cases got sent to adult court.

"When they get direct filed to adult, it's sort of this cruel wake-up call," he says.

According to Ashton, the direct file statute gives judges a "bigger toolbox" for deciding how to deal with youths who have committed crimes. It also allows for more nuances in how prosecutors across Florida's 20 circuits interpret the gravity of crimes and the potential threat a youth offender has on the overall safety of a community, criteria that arguably reflect personal values and interpretations of the law.

In a 2011 report, the U.S. Department of Justice identified Florida's direct file rate as disproportionately high compared to other states. The statute is hard to measure and easily classifiable as subjective. Human Rights Watch, in a report on juvenile justice, criticized Florida's direct file statute as an example of disparate treatment of people of color. Its report found that from 2008 to 2013, black boys in Florida were disproportionately sent to prison, whether for first- or second-time offenses.

That trend continues with data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice showing that 64 percent of kids sent to adult court in 2016 were black.

Measuring direct files across the country

Currently, 12 states and the District of Columbia allow prosecutors to make decisions on where kids end up based on a direct file statute. But one major roadblock has been measuring the consistencies and inconsistencies within the statute.

"We have pretty decent estimates of the cases that go through juvenile court, everything from race and ethnicity to age and offense. But in criminal court — the ones that go straight there because the prosecutor said so or the legislator tried to say so — largely we have no clue what those cases are all about," says Melissa Sickmund, director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice. The private, nonprofit research organization has spent 40 years collecting and analyzing data on juvenile crime and delinquency in conjunction with the federal government.

For a long time, the focus of federal and state data has been the corrections system, which has limited the ability of researchers, policymakers and juvenile justice advocates to get a clear picture of the potential and shortcomings of the adult transfer system.

Juvenile justice in most states varies from county to county, without a standardized system for documenting, analyzing and disseminating statistics on kids who commit crimes or are at risk of doing so. The tradition within the juvenile justice system has been to decide the outcomes case by case, with individual values for what is in the best interest of the child having more weight than data.

"It makes it hard to do reform," says Sickmund. "You have a good intent and say we're going to do things differently, but then a few years down the road, it's hard to say whether that was a good decision or not because you don't know where you were."

Research has shown that taking kids out of the juvenile system and putting them in the adult system makes them worse off. One way to measure the impact of direct file is through recidivism: Was a youth rearrested after being sent to adult court and dismissed? Was he reconvicted for another offense? Was it for a serious charge that would have been a felony?

In 2014, the Pew Charitable Trusts conducted a survey of juvenile corrections agencies in all 50 states as part of its Public Safety Performance Project. The survey, which focused on measuring recidivism, found that 1 in 4 states does not regularly report the data needed to assess trends in where youths end up.

The survey displays the data states were collecting at the time and their varied standards. Language to describe recidivism — and the definition of the term itself — changes from state to state and over time. No project of its nature has been done since, according to Adam Gelb, director of the Public Safety Performance Project, largely because of the level of work and coordination involved.

"There were two real takeaways from the report," Gelb says. "One was that there needs to be much greater consistency in how states are collecting this information and, second, that they've actually got to make recidivism reduction a core part of their mission, and that means tracking it; using that data to make decisions about how to respond to these kids."

States in the midst of reform

Last year saw sweeping changes across the country in the nation's direct file trend. The most dramatic shift was in California where, last November, voters approved Proposition 57, which removes the unfettered discretion given to state prosecutors. The new law requires that kids eligible for a transfer to adult court first go before a juvenile judge, who is expected to consider the youth's case and the circumstances that led to it.

Prop 57 was the result of a major effort by juvenile justice advocates, who argued that sending kids directly to adult court undermined the rehabilitative mission of the juvenile system.

They voiced concern that California's direct file statute opened the door for longer sentences and psychological trauma of being processed through adult criminal court, which meant lifelong consequences for youths and their families.

In a report, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, noted disparities across counties in how the direct file statute was used, based on the political affiliations of district attorneys and the race and ethnicities of youths. According to Maureen Washburn, a policy analyst, an overall drop in juvenile crime in California helped make a case for reform. Lower numbers of youths in the system means more capacity to strengthen rehabilitative care. Less than a year into Prop 57's implementation, advocacy groups are planning to research and evaluate transfer hearings and, eventually consider phasing them out.

"The juvenile justice system in California is prepared and poised to manage all young people regardless of the seriousness of their offense in the juvenile justice system where they can truly receive the services and rehabilitation that they need to rejoin their families and community," Washburn says.

In 2016, lawmakers in Indiana approved an unprecedented state "reverse transfer" law, which allows kids sent to adult court to be placed back in a juvenile court if their adult charges are unsuccessful. The purpose of the change is to restore the possibility of exposing a kid to rehabilitative care within the juvenile justice system. In recent years, Indiana voters have reduced the number of offenses once protected under the direct file statute. Kids accused of criminal gang activity, intimidation and substance-abuse-related acts can now be seen in juvenile court.

"But we think there's still a lot more to do," says JauNae Hanger, president of the Children's Policy & Law Initiative of Indiana, a network of juvenile justice advocates.

She argues that Indiana and other states must reconsider the age at which brains have fully developed.

"What happens to the 18- to 25-year-old? Should we be treating them differently?" Hanger asks. "That's a long-term question for our state, how we treat youthful offenders systemically."

The community and change

Before landing in front of the judge 10 years ago, Marquis McKenzie had displayed the textbook signs of an "at risk youth" navigating the complexities of community in desperate need of economic resources. He vividly recalls moving with his mother when he was 8 to the Ivey Lane Homes, a housing project in Pine Hills, a predominantly black, mixed-income neighborhood on Orlando's west side. The community, once a suburban oasis for white middle class families, had earned the moniker "Crime Hills." McKenzie remembers being exposed to gang violence, drug deals, drug busts and burglaries.

Witnessing a domestic violence incident between his mother and her boyfriend ultimately drove him to get involved in street life, he says.

"She had to get eight stitches in her head. And after that, nothing else didn't really matter. That was my excuse to be harmful to people," he says.

When McKenzie was transferred to adult court, he took a youth defendant plea. Though facing 10 hard years in prison, he served two and was placed on four years of probation, which were reduced by half due to good behavior.

"Income is one of the biggest things," McKenzie, who is now 27, says of many teenagers who get in trouble. "It's kind of hard to tell them to put the gun down or stop stealing if you don't have a direct resource for them."

Today, McKenzie has two sons, ages 7 and 4. He started his own cleaning company, called The Dirt Master LLC, and has been training to teach remodeling, so he can equip youths with skills to repair their homes and, ultimately, their neighborhoods.

"A lot of people have broken sinks, tubs, holes in the walls," he says. "And I kind of strongly believe if you change the way somebody's living, you can impact their life forever."

"You could consider other options"

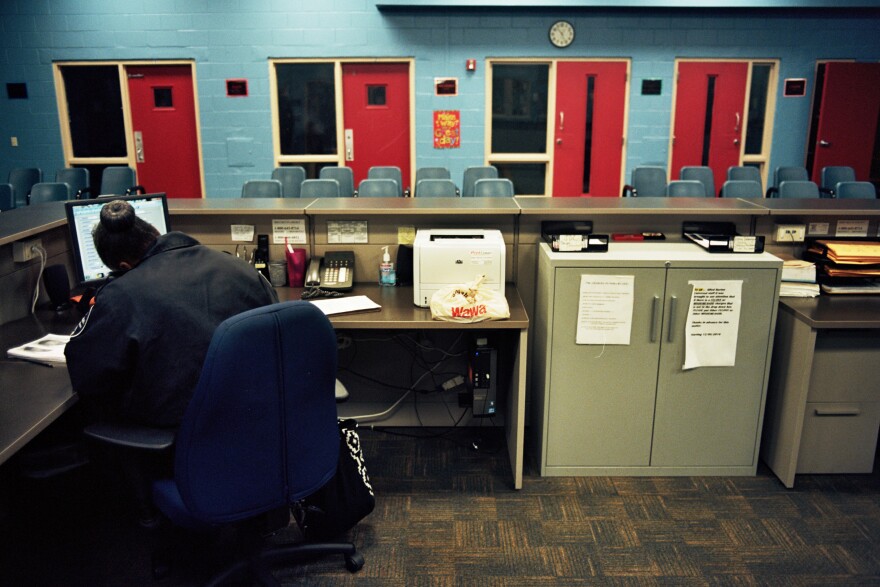

Orange County, where McKenzie was direct filed in 2007, has the highest number of direct files in Florida. And Pine Hills, where McKenzie grew up, has the highest concentration of juvenile arrests and direct files in Florida.

With support from the state attorney's office and the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, community groups there are working to fill a gap that law enforcement cannot.

Let Your Voice Be Heard Inc. has become the biggest voice in Pine Hills, hosting job fairs, talking in schools about conflict resolution, and making on-call house visits for "crisis mentoring."

"We sit down and try to figure out what the case is with that particular individual. If we don't have the expertise that the child needs, then between 24 to 72 hours, we will contact the individuals for the parent to take the child to get further assistance for that particular situation," says Emery James, who helped found the nonprofit advocacy group with Miles Mulrain.

James was direct filed to prison at 15 for an armed robbery. Now, at 38, he is developing programs to keep kids out of the system.

"I've learned firsthand the detriments of negative situations and the psychological effects that it can have on a child's mind. By the grace of God, by me going through all the trials that I did, I can look back and say 'Wow, everybody's not going to make it out like that, doing 10 years or better in the system with all of the dehumanizing living conditions."

In the past five years, Florida's Department of Juvenile Justice has visibly shifted its focus to kids' unique needs based on a set of criteria including family situation, schooling, and mental and physical health histories. The agency has a sophisticated set of data available for law enforcement to make informed decisions on where it is best for a child to end up.

Ed Brodsky is state attorney for the 12th judicial circuit. In 24 years, part of them as a former assistant state attorney, he has handled dozens of criminal cases involving adults and youths. He has noticed a significant change in the prosecution model.

When asked a decade later whether a 16-year-old with McKenzie's case and circumstances would be direct filed, he responded, "You could consider other options."

Florida's direct file rate has dropped since McKenzie was sent to adult court, and it continues to. The number of youths transferred under the direct file statute has decreased by 51 percent, from 15,665 to 7,619.

For McKenzie, that is promising, but the remnants of his past still haunt him. Earlier this year, he found himself in the back of a police car for not moving his parked car and resisting arrest for it — charges that were dropped.

"It would've been another stumbling block, especially if I'd have gotten convicted for it," he says. "[Police] already still look at the past that I have. It's like 'He's not done getting in trouble,' so it would have been even more for me to try to prove my point as a citizen out here and even for other felons who haven't made it to the point where I'm at. I'm just going to keep fighting until a door opens and my voice gets heard."

Copyright 2021 WMFE. To see more, visit . 9(MDAxODg3MTg0MDEyMTg2NTY3OTI5YTI3ZA004))