Laid off steelworker Siegfried Powell hefts cardboard boxes from a food pantry set up by his local United Steelworkers Union in Birmingham, Ala.

"Come on, sweetheart. Grab you a bag of potatoes," Powell says as he takes a load of groceries to the car for a family trying to stretch unemployment benefits.

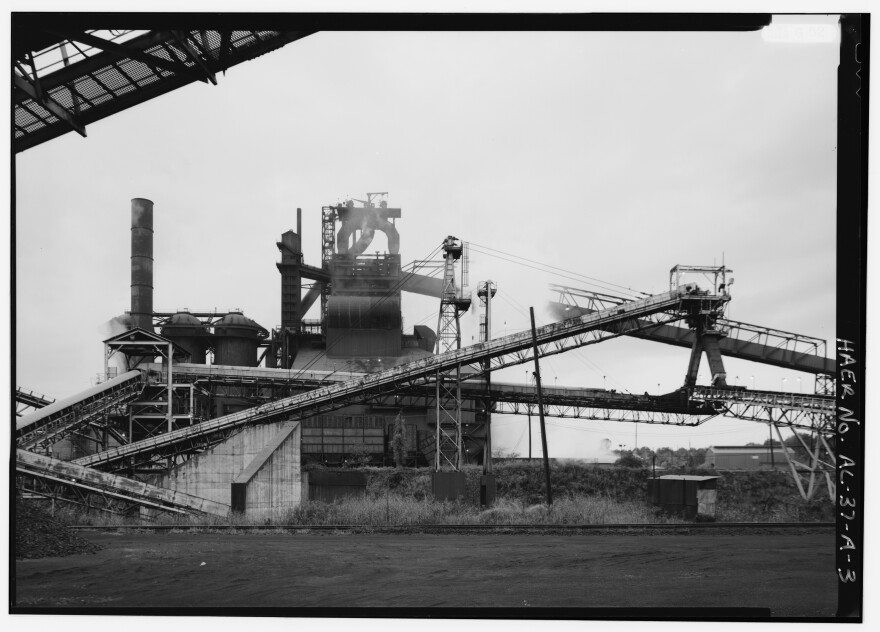

About 1,100 people lost their jobs when U.S. Steel decided to permanently close a blast furnace that had been the bedrock of Birmingham's steel industry for nearly a century.

Powell had worked at the Fairfield Works mill for 26 years; his wife, Vanessa Powell, for 18.

"We all are used to living on 40 hours a week, so we're having to make some adjustments," Vanessa says.

Working at the food pantry helps, she says. "We're giving to keep us from sitting at home stressing over what to do."

Siegfried figures that at 52, he needs more education to compete after so long in the same job.

"I'm going to upgrade a few skills," he says. "I'm not the No. 1 draft pick anymore."

Working at U.S. Steel has long been a source of pride in Birmingham. The Fairfield Works plant made steel used to build ships during World War II and since has produced steel for everything from bridge girders to railroads to household appliances.

"It's the end of an era," David Clark, president of the United Steelworkers Local 1013, says. "Birmingham was founded on iron and steel industry. It was known for years as the Pittsburgh of the South."

Located in the Appalachian foothills, Birmingham has all the natural resources needed to make iron and steel — coal, limestone and iron ore.

That led to a rich industrial heritage. And Karen Utz, curator of Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, says that for a long time, U.S. Steel was the major player.

"It was kind of the glue that held the city together for many, many years," Utz says.

She says U.S. Steel was once the largest employer in Alabama. The suburb of Fairfield was designed by the company in the early 1900s. "It was the most elaborate company town in the United States," Utz says.

But with increased foreign competition, the iron and steel industry dwindled over the decades. Utz says smaller mini-mills have replaced the giant furnaces and smokestacks that once dominated the city's skyline.

"It's a different industry today," she says. "It's probably not considered the heart and soul of Birmingham, Ala."

The University of Alabama, Birmingham, with its medical center and research spinoffs, now drives the city's economy.

At U.S. Steel, a pipe mill remains open. And the company plans to build a smaller arc furnace, which means a few hundred laid-off workers could get called back.

Clark says that still leaves a void where generations have long counted on U.S. Steel to provide. "We had grandparents, great-grandparents, fathers, sons, daughters, wives that worked here in some capacity or another," Clark says. "At one time, there was no way you lived in the area and you did not know someone who worked at United States Steel."

The Kyzers are one such family — you could say U.S. Steel was a family affair.

Debbie Kyzer's brother, nephews and brothers-in-law all worked there. Her husband is retired from the mill. Now she's laid off, and so is her 25-year-old son, Jonathan.

He was a "steel mill child," she says, who had aspirations to work there as early as elementary school. "He wrote he wanted to work at U.S. Steel like his daddy, and those were some big shoes to fill," she says.

"Growing up, for me, it was kind of a goal to get to," says Jonathan Kyzer.

He reached that goal when he was 21 and landed a job at the mill. "So I kinda figured I had the next 30 or 40 years set."

Now, instead of an assured future, there's uncertainty.

"Those times are gone," Jonathan says.

The union has been hosting job fairs, but to find jobs comparable to the ones at U.S. Steel, workers may have to leave the area for places like shipyards on the Gulf Coast, hours away.

That's a hard call for families who have been rooted in U.S. Steel.

"We all thought we would finish up and retire and leave from here," says Debbie Kyzer. "Not just be laid off and not know our future. The not knowing is what is so bad."

Donald Ferrell is also wondering what the future holds. He is president of the Steelworkers local office and technical group.

He's still working at U.S. Steel as an electric load dispatcher — basically the guy who keeps the lights on.

"There's not as many lights and they cut more off every day," Ferrell says.

He says it's a far cry from when he first started at the plant in the late 1970s, one of more than 12,000 workers.

"Steel has always been an up and down business," he says. "You'd get layoffs but you know you were coming back. Now with this, you're not coming back."

He puts the blame on trade agreements that allow cheaper imported steel into the U.S.

"Right now, because of all the foreign dumping that's going on, it's basically destroying the middle class here in this country," says Ferrell.

Steel is still an important business in Birmingham, but today it's dominated by those mini-mills that employ hundreds, not the hulking blast furnaces that provided thousands of jobs for generations.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.