Poet Safiya Sinclair grew up in Montego Bay, Jamaica, in a devout Rastafari family. Her father, a reggae singer, ruled the home, dictating what to eat, how to dress and who she could or couldn't befriend. Women were subservient, and everyone who wasn't Rasta was considered heathen.

Outside of her home, Sinclair felt ostracized for being Rasta. At school, children taunted her for her dreadlocks, and teachers treated her differently from the other students. She felt isolated and confined, but when she was 10, her mother gave her a book of poems, opening the door to a different world.

"I realized that poetry could alchemize the hurt I was feeling into something different, into something beautiful," she says. "It was through the discovery of poetry and discovery of some particular poems when I was a teenager that really lifted me from what I call the catacombs of myself."

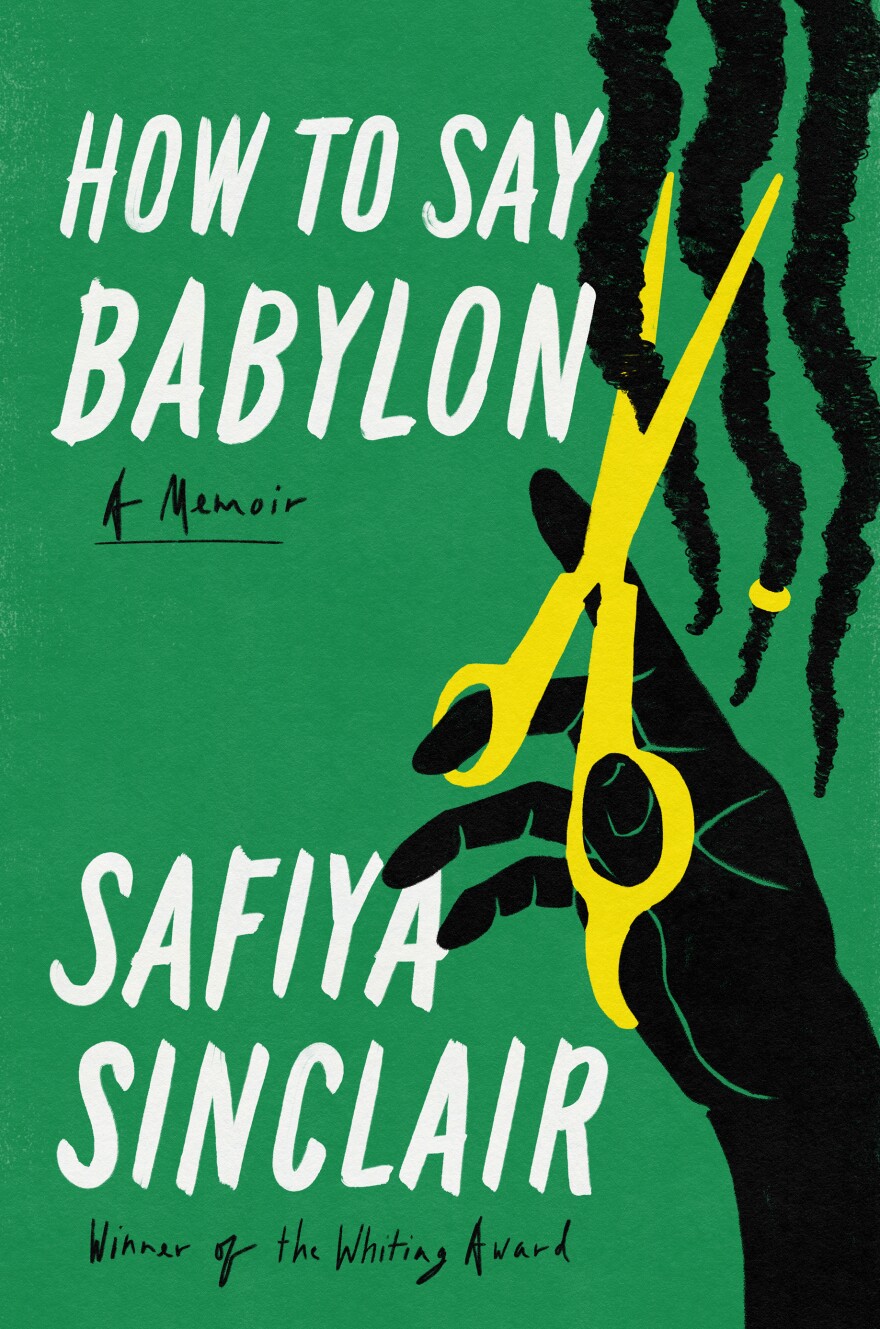

Sinclair began writing and publishing her own poetry — and questioning the Rastafari movement in which she was raised. When she was 19, she cut the dreadlocks she'd been growing for years, which infuriated her father.

"In Jamaica, when you wear your dreadlocks, it is a signifier to anyone around you that you are Rastafari," Sinclair says. After she cut her hair, she adds, "I did not exist to [my father]. I had become Babylon."

Sinclair says that it was only by leaving Rastafari that she was finally able to imagine the adult she might become. She landed a scholarship to Bennington College in Vermont, and went on to get a doctorate degree. She now teaches at Arizona State University.

Sinclair's first book, Cannibal, was a collection of poems. In the new memoir, How to Say Babylon, she reflects on her early years and her break with Rastafari.

Interview highlights

On why Rastafari were considered outcasts in Jamaica

The movement began in the early 1930s when Jamaica was still a colony of Britain. And Jamaica itself is a deeply Christian country, which I think is something that most people don't know. ... Because Jamaica is this predominantly Christian country, when the Rastafari movement began, when we were still being ruled by the British Crown, the Rastafari were seen as pariahs. They were seen as un-Christian. They were pushed to the fringes. They were kicked out of their homes by their families. They were forbidden from walking along the beach sites that were being developed for tourists. ... They were forbidden from having jobs. And so I think they were seen as the nation's black sheep. They were seen as everything anti-Christian and anti-colonial. And that was also a deliberate route of Rastafari to be anti-colonial and anti-Christian. But in a Christian society that was also seen as very transgressive and so they were not accepted.

On being raised to be pure

Purity was about how one kept your mind and your body clean. It defined what we ate. We had to eat a specific diet: ... no meat, no dairy, no fish, no eggs, no salt. That was part of the purity of the diet. Then it was about keeping your mind and your thoughts pure and dedicated to thoughts of Jah, of Black liberation, of working toward repatriation to Zion, which is the Rastafari term for Africa, seen as the motherland. For women in particular, purity also extended to a kind of restriction on our bodies. And so what I wore was part of my purity. I had to cover my arms and knees. I could wear no makeup, no jewelry. All of that was seen as the garish trappings of Babylon. And eventually, I was not allowed to have friends. Any kind of outside influence was seen as corruptive. Most essentially, I was not allowed to question my father.

On cutting ties with Rastafari

I had this moment when I was 19 and I just tried to look into the future of, OK, if I continued on this path of Rastafari, if I did all the things my father wanted me to do, if I became the woman he wanted me to be, who is she? Who would she be like? And she appeared to me as this, like, bent and broken Rasta woman who was silent, whose only value in this world is to be domestic and to be in the kitchen and to have children and to be sort of the extension of our Rasta brethren, who was the Godhead of his household. She would have no dreams or desires. She would have nothing to say in the world. She would have no art. She wouldn't have her poetry. That is the vision that came to me, and I realized I had to completely cut this woman down. I had to cut everything about her and her possibilities away from me. And that's when I decided to cut my dreadlocks and to sever the tie between me and Rastafari, and between me and my father, and to really try to offer a future that was mine, only, to make.

On how she views reggae music and dreadlocks now

Being from Jamaica, everybody wants to tell me their story that they know about Jamaica, when they went on vacation to Jamaica and how much they loved Bob Marley in college and things.

I always look at it with amused curiosity. Being from Jamaica, everybody wants to tell me their story that they know about Jamaica, when they went on vacation to Jamaica and how much they loved Bob Marley in college and things. ... But I always hear my father's voice, funnily, when I see people wearing the dreadlocks because knowing how much it means to him and the other brethren of Rastafari and other people of Rastafari, what significance it has to them. But so many people around the world aren't aware of that significance or aren't aware of all the nuances of Rastafari culture beyond reggae music and Bob Marley.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Ciera Crawford adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.