For this year's Best Books of the Year list, I reject the tyranny of the decimal system. Some years it's simply more than 10. Here, then, are my top 12 books of 2014. All of the disparate books on my list contain characters, scenes or voices that linger long past the last page of their stories. In fact, The Empire of Necessity by Greg Grandin, which is my pick for Book of the Year, came out in January and I haven't stopped thinking about it since.

Copyright 2024 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Maureen Corrigan's Top 12 Books Of The Year

Dept. Of Speculation

by Jenny Offill

The Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill is a slim novel whose lingering emotional aftereffects belie its size. It follows a young woman as she haltingly moves through marriage and motherhood in a Brooklyn apartment raddled by the urban blight of bedbugs and the maternal torment of colic. Her husband's infidelity, however, is what slams our heroine to a full stop. Offill's departures from traditional narrative form make this age-old story feel painfully fresh again: Fragmented chapters and looping monologues accord with our heroine's shell-shocked frame of mind. For instance, a chapter titled "How Are You?" is followed by these two words hauntingly repeated by our betrayed heroine for a page and a half: "soscared soscared soscared soscared ... "

Florence Gordon

by Brian Morton

Brian Morton's superb novel Florence Gordon features a 75-year-old woman — an icon of the second wave women's movement — as its heroine. She's a self-described "difficult woman," in the intimidating Lillian Hellman, Susan Sontag, "Lioness in Winter" mode. When a glowing review of Florence's latest book appears in the Sunday New York Times, she's showered with the popular acclaim that has eluded her most of her life. Suddenly, Florence is embarking on her first-ever book tour, dealing brusquely with fawning female fans of a certain age, parrying with some patronizing younger feminists and, along the way, sensing the chill of mortality on her skin.

Dear Committee Members

by Julie Schumacher

One of the reasons Dear Committee Members is such a mordant minor masterpiece is that Julie Schumacher had the brainstorm to structure it as an epistolary novel. This book of letters is composed of a year's worth of recommendations that our antihero — a weary professor of creative writing and literature — is called upon to write for junior colleagues, lackluster students and even former lovers. The gem of a law school recommendation letter professor Jason Fitger writes for a cutthroat undergrad whom he's known for all of "eleven minutes" is alone worth the price of Schumacher's book.

Schumacher has a sharp ear for the self-pitying eloquence peculiar to academics like the fictional Fitger, who feel that their genius has never gotten its due. His resentment seeps out between the lines of the recommendation letters he relentlessly writes — or ineptly fills out on computerized questionnaires — urging RV parks and paintball emporiums to hire his graduating English majors for entry-level management positions. Dear Committee Members serves up the traditional satisfactions of classic academic farces like David Lodge's Small World and Kingsley Amis' immortal Lucky Jim, but it also updates the genre to include newer forms of indignity within the halls of academe.

10:04

by Ben Lerner

Ben Lerner (Leaving the Atocha Station) is known for writing fiction that defies categories; he continues to defy — and fascinate — in this latest novel, 10:04. Bookended by two historic hurricanes that threatened New York City (Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy) 10:04 projects our narrator into plotlines that feature a dire medical diagnosis as well as the joy of impending fatherhood with a woman who's a close friend. Lerner's dazzling writing connects and collapses these and other storylines into a rich and strange novel of ideas.

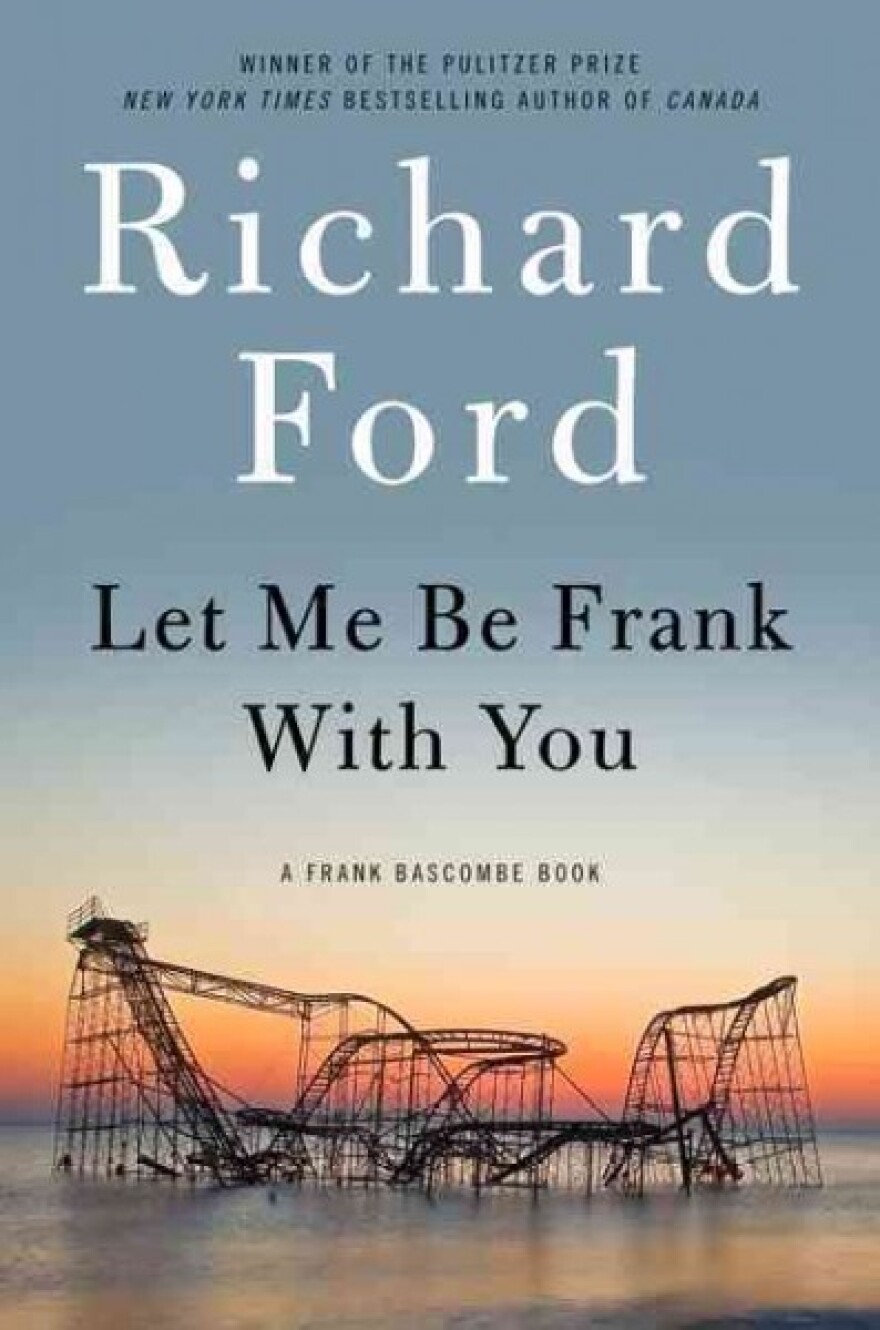

Let Me Be Frank With You

by Richard Ford

It's been eight years since The Lay of the Land was published — the novel Richard Ford said would be the last in his Frank Bascombe trilogy. Luckily, Ford had second thoughts. Frank is now a 68-year-old retired real estate broker. The four stories herein all take place in the early winter of 2012, soon after Superstorm Sandy slammed into the Jersey Shore. The cover of Let Me Be Frank With You features a photo of the Seaside Heights roller coaster that was washed out into the Atlantic Ocean. It's the most iconic image of Sandy's wrath, and it's also an iconic image for Ford's achievement throughout his Frank Bascombe books — books that chart the whole wild roller coaster ride of life.

Something Rich And Strange

by Ron Rash

Ron Rash's writing is powerful, stripped down and very still: It takes you to a land apart, psychologically and geographically, since his fiction is set in Appalachia. Thirty-four of Rash's best short stories from the past 20 years have just been published in a collection called Something Rich and Strange. They are that, indeed. Some of these stories are cold to the bone; others are empathetic and even funny. A few are set during the Great Depression and the Civil War; most, though, take place in the present — an era when illegal ginseng plots and meth labs have supplanted the moonshine stills of an earlier generation, and family farms have given way to vacation home developments. Rash, however, is no nostalgic mountain minstrel bemoaning the loss of the good old days. If it's wood smoke and sylvan sentimentality you're yearning for, you'd be better off watching reruns of The Waltons. Rash's spectacular stories may originate in the peculiar soil of Appalachia, but their reach and their rewards are vast.

The Paying Guests

by Sarah Waters

Sarah Waters' The Paying Guests is a knockout, which isn't a word any of her characters would use. Waters' novel opens in 1922: The Edwardian Age with its high collars and long skirts is dead; the Jazz Age is waiting to be born. At least, that's the case in the suburban backwater of London where Waters' main character, a 26-year-old spinster named Frances Wray, lives with her mother. The Wray women have decidedly come down in the world: Frances' two brothers were killed in World War I and her recently deceased papa made some bad investments. When the novel opens, the Wray women are awaiting the arrival of a necessary evil — lodgers — to help them cover the costs of keeping up their dark and drafty suburban villa. Shortly thereafter, an even more shocking intruder — sexual passion — steals into that house, and chaos erupts. The Paying Guests is one of those big novels you hate to see end — especially since you sense the end might be a very nasty one, indeed.

All The Light We Cannot See

by Anthony Doerr

Anthony Doerr's magical adventure novel All The Light We Cannot See takes place in France and Germany in the years leading up to and during World War II. A blind French girl and her father become the hapless custodians of "The Sea of Flames," a rare (and accursed) diamond that Hitler desires for his personal treasure-trove. Meanwhile, a German orphan boy proves himself to be so ingenious at mastering higher-level mechanics that he is selected for an elite Nazi training program. Toward the end of the war, these two tempest-tossed adolescents are thrown together in a climactic twist of fate that no reader could possibly anticipate. Doerr refers to the work of Jules Verne and Alexandre Dumas, and his own sweeping plot and sumptuous language place Doerr in the same category as those master storytellers.

The Secret Place: A Novel

by Tana French

The Secret Place, Tana French's fifth Dublin Murder Squad novel, pries open the world of teenagers at a girls' prep school, and the homicidal stew of hormones that lurks within could chill the toughest detective's blood. Detective Stephen Moran turns up at St. Kilda's School outside Dublin in search of answers to a cold case. One of the students has contacted Moran with teasing information about the death of Chris Harper, a Casanova from a nearby boys' school whose corpse was discovered on the grounds of St. Kilda's the previous year. French is sensitive to the look and manner of mean girls and the subtle tortures they so deftly inflict on their victims.

Deep Down Dark

by Hector Tobar

It was a miracle watched around the world on live TV. On Oct. 13, 2010, 33 Chilean miners trapped for 69 days inside the San Jose mine were raised to the surface of the earth — resurrected — through a freshly drilled escape tunnel into which a capsule was lowered and raised by a giant crane. Before they escaped, all 33 men agreed to share the proceeds of any book or movie made about them. The movie is in the works. The book, written by Héctor Tobar and which came out in October, is called Deep Down Dark. As extreme adventure tales go, this one is a doozy — the equal, if the geographical inverse, of Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer's 1997 blockbuster about the Mount Everest climbing disaster.

Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

by Roz Chast

Who would have expected that the most profound meditation yet written on the trials of caring for aging parents would arrive in the form of a graphic book? Chast's memoir is a masterpiece, describing the exhaustion and absurdity, the anger and heartbreak of this cosmic Life Switcheroo that so many of us boomer-generation readers are experiencing. From the sad looniness of having to clean out her failing parents' Brooklyn apartment (whose closets are stuffed with toasters — still in their boxes! — and old bank books) to the desperate anxieties over the astronomical costs of end-of-life care, Chast captures the totality of the "adult child of elderly parents" experience. Brava!

The Empire Of Necessity

by Greg Grandin

In Fordlandia, historian Greg Grandin chronicled Henry Ford's attempt to establish a utopian version of small-town America in the middle of the Brazilian rain forest. In The Empire of Necessity, Grandin shows readers the hell of the slave trade. His touchstone is the true-life slave revolt in 1805 on a ship called the Tryal. (Herman Melville drew almost exclusively upon the story of the Tryal to write his own floating Gothic masterpiece of a short novel, Benito Cereno, in 1855.) Grandin tells the harrowing story of the 72 desperate slaves aboard the Tryal to fan out and explore the explosion of the slave trade in the Americas in the early 19th century. The Empire of Necessity is a wonder of power, precision and sheer reading pleasure about human horror and degradation.