I met Aaron Garcia one day outside an Allsup's gas station and convenience store near my home in Santa Fe. I would hang out at this particular Allsup's for hours at a time, multiple days a week, and introduce myself to all the people that came by.

At the time, I was an artist who had just moved to New Mexico in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. With no friends, no community and no job, I saw it as a way for me to meet people that lived around me, while also being an exercise in being vulnerable.

Little by little, I became known as the gas station photographer, but it was Aaron who really invited me to become part of this community. There was an instant connection between us, and before I knew it, we were talking about rocks and feathers, jewelry, ashes, and how intense New Mexico can be.

Aaron also asked me what I was doing standing around at the Allsup's, and told me he sensed a lack of home within myself. He taught me many things about myself that were kept hidden and brought them to the surface, all while bringing a smile to my face.

I don't think I have ever been understood by someone in the way Aaron recognized me. I realize now that Aaron did this with everyone, and it's because he saw himself in everyone.

During our first encounter at Allsup's, I asked Aaron if he wanted to embark on a project with me. Though I did not know what the project would become at the time, it's clear to me now that the project was us — our friendship.

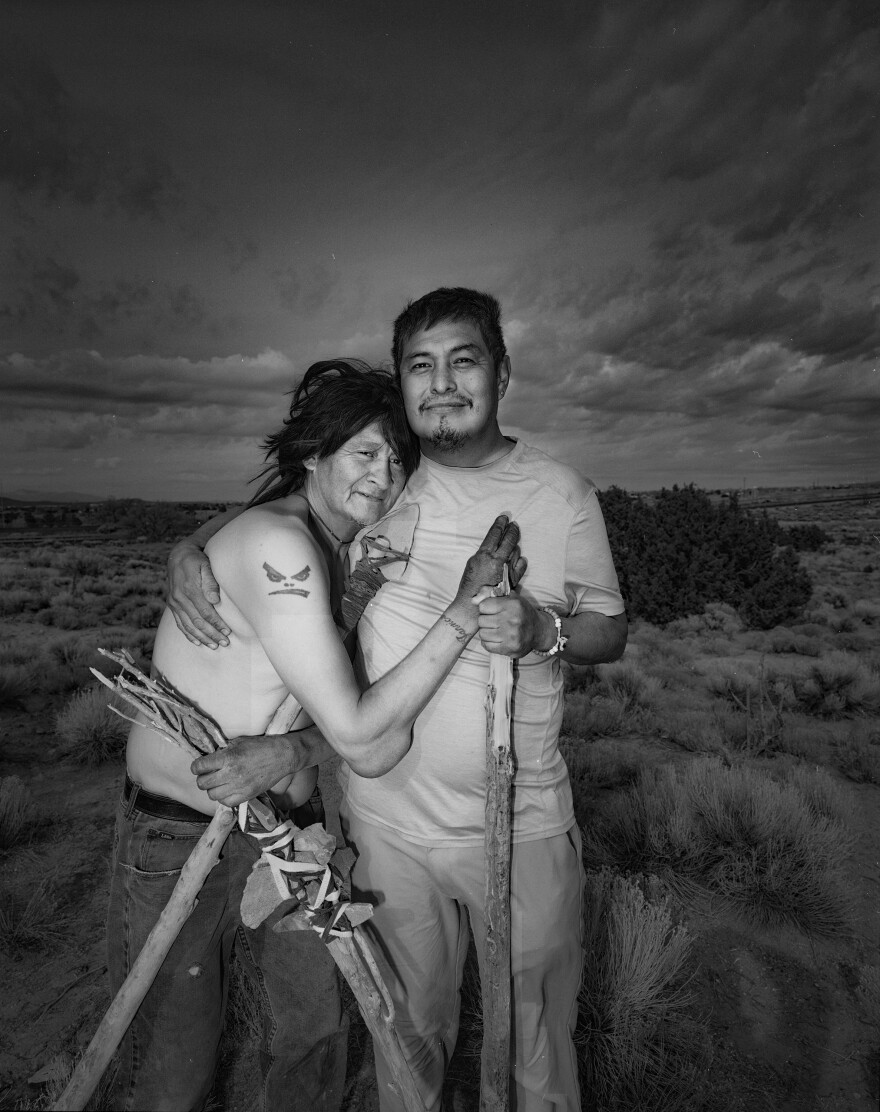

Aaron and I were very different. He was a 48-year-old Native American from New Mexico, and I was a 23-year-old Cuban American from Miami. Together, we started making a visual record of his life, along with his younger brother, Russell Garcia, and other men who lived with Aaron and wanted to participate in sharing a part of themselves without fear of shame or judgment.

I remember asking Aaron why he chose to live outside when he had a home in Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo Pueblo), and he told me stories of his experiences at a place called Camp Tule in California where he got to live his Native beliefs and traditions in a deeper way. When the retreat was over, Aaron remained dedicated to living in nature, choosing a spiritual victory against the social expectations surrounding living standards.

Prior to all of this, Aaron had been living with his mother and working all sorts of jobs. He was also volunteering as a firefighter and attending to duties in the Pueblo.

I would visit Aaron every day, and would learn more from him, which only drew me closer to him. I learned that Aaron's nickname was Pillar. In fact, he was given this name for his leadership and protection regarding many travelers, drifters and people without houses.

Aaron cooked for people, provided shelter for many during harsh weather and drastic changes in temperature, helped some find work, and brought relief to many through laughter and joy.

It wasn't long before Aaron, Russell, myself and other guys were squeezing into my car and going on camping trips around New Mexico, or before I would invite them all over for dinner and a movie.

That all changed at around 9 p.m. on Sept. 22, 2023, when Octavia, Dustin's girlfriend, texted me to say that a body had been found under the overpass near Aaron's campsite.

Dustin, who was living with Aaron at the time, had told her, but he didn't know what had happened. A heavy, uneasy feeling overcame me, and my gut feeling was "Aaron is dead," so I rushed to the campsite.

Detectives stopped me as I arrived on the scene to ask me questions. They couldn't confirm who had died without an autopsy, but after physically describing Aaron to them, they told me the probability was high that the body was his.

For the next two days, I received calls from detectives asking me questions; and then suddenly, I heard nothing at all. It was like it had all disappeared and been forgotten about.

The response I got the last time I reached out to ask the detectives about Aaron's case, the detective's response was, "Who's Aaron?" After jogging her memory, I was told the case had been transferred to another detective.

I have continued to make calls to the Santa Fe Police Department, as well as the detectives assigned to Aaron's case, but have not been able to actually communicate with anyone. If I don't reach someone's voicemail, I'm left on hold for hours and hours. As far as I know, there has been no resolution to the case, and I doubt there will ever be justice for Aaron's murder.

When I went back to Aaron's campsite a few weeks after his death, I was surprised to see it was exactly how he'd left it — nothing was roped off, no crime tape, and nothing to show a murder had occurred. It didn't resemble a crime scene at all; it felt like I was visiting him again, and like I was just waiting for him to poke his head out from behind the juniper bushes and call my name.

As I was standing there at the campsite, a man walking by on a trail approached me. He asked me if I was alright and asked if I knew what had happened to the homeless man who'd lived there. I told him I did, that I knew Aaron and that's why I was down here, under the bridge. He continued his walk and left me standing there.

On my drive home, I thought about Aaron and realized that he had never once described himself as a homeless person. It triggered me into thinking about all the people who had dismissed Aaron for being "homeless" or a "homeless Native" without ever talking to him and giving him the time to be a person.

Now, even in his death, I still found him being disregarded, or looked upon as an afterthought, as someone who wasn't important. But the truth of the matter is that Aaron was a special beacon of support.

I have been reflecting on the past three years I spent with Aaron, his younger brother, Russell, his mother, Mary, and other members of his family, as well as the community at the Allsup's near my home.

A lot of my time with Aaron and Russell was spent helping them navigate authority figures and institutions and learning you constantly have to fight and pressure people for answers or some sense of acknowledgment. Whenever I went with Aaron to the hospital to get his physical pain checked out, or gave him a ride to the grocery store, to Walmart, or to the laundromat, it was the same kind of dismissive inferior treatment.

If Aaron could see himself in everyone, why couldn't we see ourselves in Aaron? He told me once that all people want to do is smile and feel good about themselves, and that we all belong to love. Regardless of age or gender, occupation, or any kind of trouble you might be in, Aaron spoke to you, looked at you, and ate with you like you were his best friend.

You're given an opportunity to reaffirm someone's life, as well as your own, every time you ask: "How are you doing today?" and mean it. By sharing these images and Aaron's life over these last three years, I not only want readers to stop and see themselves in Aaron and these men, but I want to show the value in connecting with a stranger.

You can find more of Andrés Mario de Varona's work at AndresMario.com or on Instagram at @andres.deva.

Tsering Bista photo edited this story.

Zachary Thompson copy edited this story.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.