Updated May 9, 2023 at 1:54 PM ET

Fox News' abrupt firing of star Tucker Carlson has caused such an uproar over the past two weeks that it has obscured profound questions about its corporate board and its controlling owners, the Murdochs.

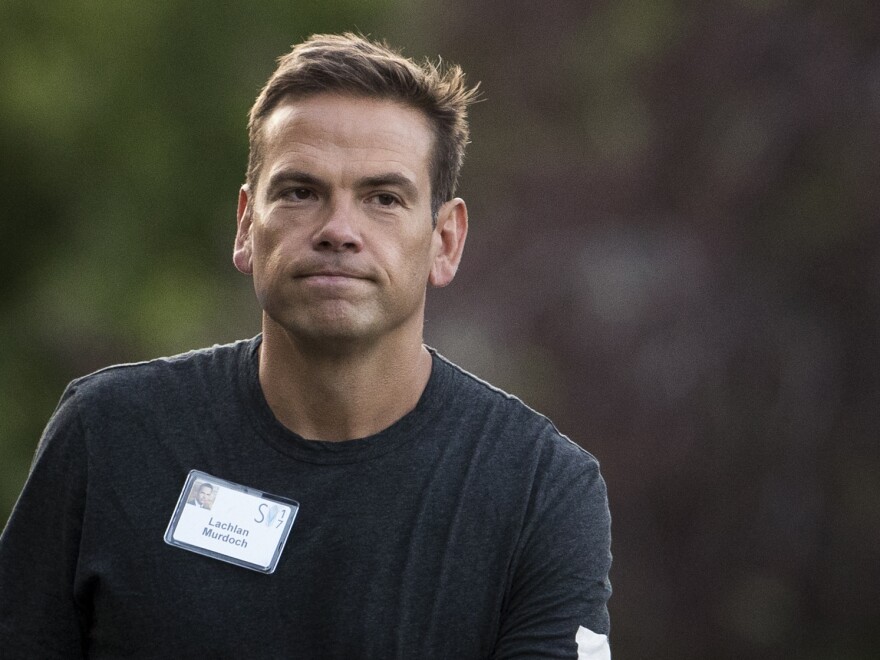

In speaking with investors on Tuesday, Fox Corp. executive chair and chief executive Lachlan Murdoch did not apologize for the network's repeatedly broadcasting bogus claims that Dominion Voting Systems conspired to cheat then-President Donald Trump of victory in 2020.

Instead, he said, "we always acted as a news organization reporting on the newsworthy events of the day." Fox is on strong legal, financial and professional footing, he added, in a call just three weeks after the company agreed to pay $787.5 million to settle Dominion's defamation lawsuit. Murdoch called the settlement a business decision "clearly in the best interests of the company and its shareholders."

Nor, despite questioning, did the Fox boss detail why he fired Carlson, Fox's top star who has developed into one of the most influential figures in Republican politics and whose departure has sunk Fox's prime-time ratings, at least for the moment.

Carlson, who was one of the stars targeted by Dominion, is also the focus of an ongoing lawsuit from one of his senior producers who alleges a workplace rife with bigotry and sexism. He tells NPR he knows nothing about her. Fox says her accusations are meritless. Major advertisers had already abandoned Carlson's show, which regularly embraced groundless conspiracy theories and made appeals broadly found to be racist, xenophobic and misogynistic.

Despite waves of speculative reports, the Dominion settlement and Carlson's ouster were born of a desire to tidy up messes and move on, according to three people with direct insight into decisions made at Fox. That also applies to what viewers have — and have not — seen on the network about the twin controversies: no apologies, no retractions and few specifics on what transpired. The Murdochs, one associate said, want these controversies in the rear view mirror.

Fox's Howard Kurtz says other news outlets "were aiding Dominion"

And that desire is reflected by what Fox broadcasts. For months, as other major news outlets detailed damning revelations that surfaced in the pretrial phase of Dominion's suit, Fox barely touched the subject on the air.

In late February, Fox media host and correspondent Howard Kurtz told viewers the network was not allowing him to cover the case. He said he disagreed with the decision because the lawsuit was "a major story."

In mid-April, on the eve of the trial, Kurtz said on his Sunday show that he would cover it "fair and down the middle" and acknowledged some adverse rulings to Fox by the judge in the case. Kurtz shared few of the details that were so damaging to Fox, however.

Two days later, the company announced a settlement. Kurtz went on the air, but did not tell viewers the $787.5 million price tag, saying he could not independently confirm it. Fox host Neil Cavuto, bemused, cited the Murdochs' Wall Street Journal in announcing the figure, which Dominion's attorneys had given at a nationally televised press conference. Fox Corp. filed federal documents attesting to the number the next day.

That Sunday, Kurtz devoted four minutes to the settlement. About three of those minutes were spent restating the network's legal defenses, defending his own coverage, and assailing press coverage of the case by other outlets.

"The overwhelming majority of media outlets were strongly against Fox, and therefore were aiding Dominion," Kurtz said. A spokesperson said the network declined to make Kurtz available to be interviewed for this story.

Asked several times and in detail whether Fox, in retrospect, regretted its treatment of the election-fraud claims, the network spokesperson declined to comment. Instead, she issued a statement saying Fox has significantly increased its investment in journalism in recent years.

"Shocking, striking, outrageous"

As a matter of journalistic practice and sound corporate leadership, Fox's no-regrets approach flies in the face of reality, many observers say.

"What I saw was shocking, striking, outrageous," says Frank Sesno, a former CNN Washington bureau chief and news executive who was poised to testify as an expert witness for Dominion on professional standards in television news.

"It's a corporate governance nightmare," says Nell Minow, the vice chair of ValueEdge Advisors, which counsels major institutional investors.

"Something went wrong," says Charles Elson, a lawyer and founding director of the Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware's business school.

Texts and emails disclosed in the Dominion case showed most Fox journalists, executives and corporate officials did not believe the claims of election fraud from Trump and his allies. The network aired them anyway to win back viewers who peeled away after the conservative network was the first to project that Joe Biden would win Arizona.

What happened at the time and since represents a dual failure, the network's critics argue.

First, executives did not act to prevent Fox's hosts from amplifying and, in some cases, endorsing false claims that Dominion committed election fraud, despite knowing those claims to be untrue. These observers note the company also failed to apologize afterwards publicly or on its programs.

Most news outlets hold that correcting the record on fatally flawed stories is fundamental to retaining public trust. CBS News retracted a story about the deadly debacle at the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, based on claims from an unreliable source. The Washington Post corrected accounts of allegations against Trump that did not hold up. Fox has not retracted or appended editors' notes to any of the segments in question.

By design, Fox's power rests in the Murdochs

Second, Minow and Elson say, Fox suffers from a failure of corporate accountability rooted in the same cause: The Murdoch family's utter control of the company. Because of the structure of both the company and his family trust, Fox founder Rupert Murdoch is considered to control more than 42% of Fox Corp.'s voting shares, despite owning a small fraction of the company's overall stock, according to the annual report it filed last summer.

Says Minow: "Any time that you've got the insiders with a disproportionate amount of control, you're asking for trouble. And any time you've got a succession plan based on who was born to whom, rather than who's the best person, you've also got a problem."

Through a corporate spokesperson, Fox Corp., its executives and its directors declined to comment for this story.

A shareholder derivative lawsuit filed late last month suggests that the lack of corporate efforts to stop the spread of baseless election claims comes at a cost – more than three quarters of a billion dollars so far, and counting. (The figure represents about two-thirds of the net profit Fox reported to government regulators last year.)

Dominion isn't the only company intent on making Fox pay for such claims. Smartmatic, another voting technology company, is suing Fox for $2.7 billion over the broadcasting of similarly groundless claims. Fox canceled the show of Lou Dobbs, the top-rated star on the Fox Business Network, the day after Smartmatic filed its suit in February 2021.

Shareholders say Murdochs and Fox board to blame for events that led to litigation

"The exposure to the litigation claims of Dominion and Smartmatic, as well as the reputational harm and economic injury to Fox from, among other things, defending these lawsuits, could easily have been materially mitigated had FOX given an early, timely, full-throated, widely published retraction," reads the suit, filed in Delaware Chancery Court on April 25. "But the Director Defendants knowingly failed to cause FOX to do so, sitting motionless and mute in the face of known duties to act and speak."

Put simply, had Fox corrected the false statements promptly and prominently, the network and its parent company wouldn't be in such dire legal and financial straits, the argument goes.

It is the second lawsuit brought by Fox shareholders following the Dominion settlement. Both witheringly scrutinize the Murdochs' judgement.

In the aftermath of the elections, the two Murdochs shared Fox News chief executive Suzanne Scott's frustration with the network's journalists, especially those seeking to fact-check false claims, even as they did not believe those claims to be true. While he testified under oath earlier this year that four of his stars endorsed the election fraud lies to some degree, the elder Murdoch seconded Scott's efforts to placate its viewers at the time rather than present them with hard truths.

Board members Paul Ryan, the former U.S. House Speaker, and Anne Dias, a wealthy investor who runs her own hedge fund, separately warned the Murdochs that the network needed to explicitly reject Trump's conspiracy theories and stop entertaining their proponents. Those cries went unheeded; neither has publicly broken with the company. Fox did not make the Murdochs or other directors available for comment.

"The board is elected by the shareholders to ensure that management is acting effectively and with appropriate probity. And part of that is ensuring that the company doesn't get itself into legal trouble for actions the company may take," says the University of Delaware's Elson. "Where was the board?"

Among the members of the board at the time (and currently) are former Ford Motor Co. CEO Jacques Nasser, the lead independent director who has served as a paid corporate director of one major Murdoch venture or another for more than 20 years, and Chase Carey, who previously served as a Murdoch executive for decades.

At times the Murdochs make moves that make sense to the family and few others beyond their orbit. They wanted to reunify their television and publishing holdings — Fox Corp. and News Corp — in a deal that found few external fans. The Murdochs were not allowed to cast their votes on the deal, and its prospects appeared doomed as criticism of their leadership grew louder. The companies withdrew the proposal early this year.

Fox cites "First Amendment freedoms" in battling Smartmatic defamation suit

The company says it is girded for Smartmatic's suit: "We will be ready to defend this case surrounding extremely newsworthy events when it goes to trial," Fox said in a statement released by a spokesperson. "Smartmatic's damages claims are implausible, disconnected from reality, and on its face intended to chill First Amendment freedoms."

Fox attorneys, reiterating their initial defense against Dominion, say the network simply relayed newsworthy claims about the 2020 elections by newsworthy people: the sitting U.S. president and his allies.

Fox officials say the judge overseeing the Dominion case knocked out key elements of their defense, and that, should Smartmatic's day arrive, it'll be a new day in a new courtroom. Lachlan Murdoch repeated the point on Tuesday, saying the Smartmatic case "is a fundamentally different case than Dominion, in that all of our full complement of First Amendment defenses remain, and we'll be ready to defend this case surrounding extremely newsworthy events."

In its statement at the time of the Dominion settlement, Fox acknowledged only "the Court's rulings finding certain claims about Dominion to be false."

It continued: "We are hopeful that our decision to resolve this dispute with Dominion amicably, instead of the acrimony of a divisive trial, allows the country to move forward from these issues."

Dominion's chief executive and attorneys, by contrast, say Fox's whopping payment amounts to a concession of wrongdoing.

Fox producer: "I couldn't defend my employer"

Fox's on-air indulgence of falsehoods about fraud in the 2020 election haunted its journalists. Reporters fired off anguished notes to one another. Anchor Bret Baier repeatedly and fruitlessly asked executives if he could host an hour-long special fact-checking the false claims, even as he privately shared Carlson's anxieties about losing viewers. A producer on Baier's evening political newscast Special Report privately told a colleague he would leave the network, angered that several anti-Trump conservative voices were bumped from the show.

"The post election coverage of 'voter fraud' was probably the complete end," the producer, Phil Vogel, wrote. "I realized I couldn't defend my employer to my daughter while trying to teach her to do what is right."

Vogel's message was made public during the Dominion litigation.

Sesno, the former CNN Washington bureau chief, says Fox could have redeemed itself, in a sense, by squarely covering the questions raised in the Dominion lawsuit. It did not do so, he says.

"Fox can't call itself a news organization if it isn't going to observe the most fundamental practices and premises and principles of journalism," Sesno tells NPR. "If they want to have news in their middle name, then they need to operate like a news organization. Seek truth, update stories, correct mistakes. Be accountable for what you're reporting. Don't pander to your audience. Bring your audience the truth, the information that they need that reflects reality."

At no point, says Bill Grueskin, a former top editor at the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News, did Fox set out for its audience the chasm separating what documents show its journalists and executives knew about the 2020 elections and what it actually aired.

"That's what made all of the snippets that dribbled out so compelling, because they showed you what's going on behind the scenes," he says. "Everybody already knew that [hosts] Lou Dobbs and Maria Bartiromo had been peddling these falsehoods about the election. What we didn't know until now was the extent of how management, from Rupert on down, was dealing with it."

Inside the network, staffers question whether Bartiromo and several other leading figures, including CEO Scott, will keep their jobs for long.

On Tuesday, Lachlan Murdoch praised Fox's performance but did not mention Scott by name, as he has in the past. "We're proud of our Fox News team, the exceptional quality of their journalism and their stewardship of the Fox News brand," Murdoch said.

In a statement for this story, Fox says it remains committed to covering the news.

"We are incredibly proud of our team of journalists who continue to deliver breaking news from around the world," the statement reads. "FOX News has significantly increased its investment in journalism over the last several years, further expanding our news gathering commitment both domestically and abroad while providing state-of-the-art resources to enhance our coverage. We are incredibly proud of our team of journalists who continue to deliver breaking news from around the world to our diverse audience."

Fox pays when necessary, apologizes as a last resort

In settling with Dominion last month, Fox's public statement did not entertain any hint of an apology. Instead, it asserted the deal reflected its "continued commitment to the highest journalistic standards."

Rejecting contrition is a consistent Murdoch trait: the family's properties rarely apologize unless forced to do so.

It took 22 years for the Murdochs to apologize for the Sun tabloid's coverage of a stadium stampede that cost 96 British soccer fans their lives in 1989. The reports wrongly blamed the behavior of the fans themselves. The apology was delivered by his younger son James in 2011 during a full-bore national scandal over the Murdoch tabloids' efforts to hack into the voice mails and emails of people their tabloids were attempting to cover.

The Murdochs apologized for the hacking too, as they sought to preserve their ability to acquire full possession of a major British satellite TV company. They ultimately failed.

Two years later, in 2013, the Murdoch's publishing wing paid $139 million to settle a shareholder derivative lawsuit over disclosures from the hacking scandal. In 2017, an earlier incarnation of Fox Corp. agreed to pay $90 million to settle similar suits filed after a raft of sexual harassment allegations consumed Fox News. The scandals prompted the ouster of the network's late chairman, Roger Ailes, star Bill O'Reilly and others. Insurers footed both bills in the shareholder suits.

Those dollar amounts do not include other major costs, including payments to victims of such actions, including $20 million to former Fox host Gretchen Carlson. Fox did publicly apologize to Carlson, who used her iPhone to tape Ailes' sexual advances. (Before his death, Ailes denied all such accusations. O'Reilly has done the same.) The estimated cost of the tabloid hacking scandal exceeds $1.4 billion, according to Press-Gazette in the U.K. (James has since severed ties with the Murdoch family's media properties, citing differences over news coverage.)

False boasts of no corrections

At Fox, Ailes used to boast that Fox never had to correct a story, even though that assertion was blatantly untrue.

When Fox withdrew a story in 2017 that baselessly claimed that the late Democratic party staffer Seth Rich had leaked thousands of emails to Wikileaks during the 2016 campaign, it merely said the story did not meet its standards. It later paid millions of dollars to settle a suit brought by Rich's family, publicly saying it hoped the resolution brought the family solace. It did not apologize or explain what went wrong.

According to the Washington Post, Rupert Murdoch rebuked star Laura Ingraham for apologizing a few years ago after she made offensive remarks about a teen activist who had survived a mass shooting at his Florida high school. Murdoch said it made her and Fox look weak.

Minow says the Murdochs' record reflects a recklessness born of near-impunity, that they pay to make problems disappear when they must and apologize only grudgingly because of the virtual stranglehold they have on company affairs. She notes Delaware Superior Court Judge Eric M. Davis told Fox's legal team it had misled the court over Rupert Murdoch's role at Fox News and announced an investigation of whether it had made other false representations before the Dominion case settled.

Originally, Rupert Murdoch's media holdings were incorporated on the Australian Stock Exchange in his home country. In 2004, he re-incorporated the company in Delaware, which empowers executives to a greater degree. He promised several concessions to assure investors that they would have protections approximating those given to independent board members and shareholders in Australia.

As a 2010 Vanderbilt Law Review article documented, the Murdochs quickly broke those and other promises.

Minow says the structural changes she believed are needed are unlikely to take place: removing the Murdochs' chokehold over the voting shares of the company.

Instead, she offers this prediction: "I think the biggest change that this company is going to make right now is there will be no more texting between the people who work there."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.