In Florida, archaeologists are investigating a site that a century ago sparked a scientific controversy. Today, it's just a strip of land near an airport.

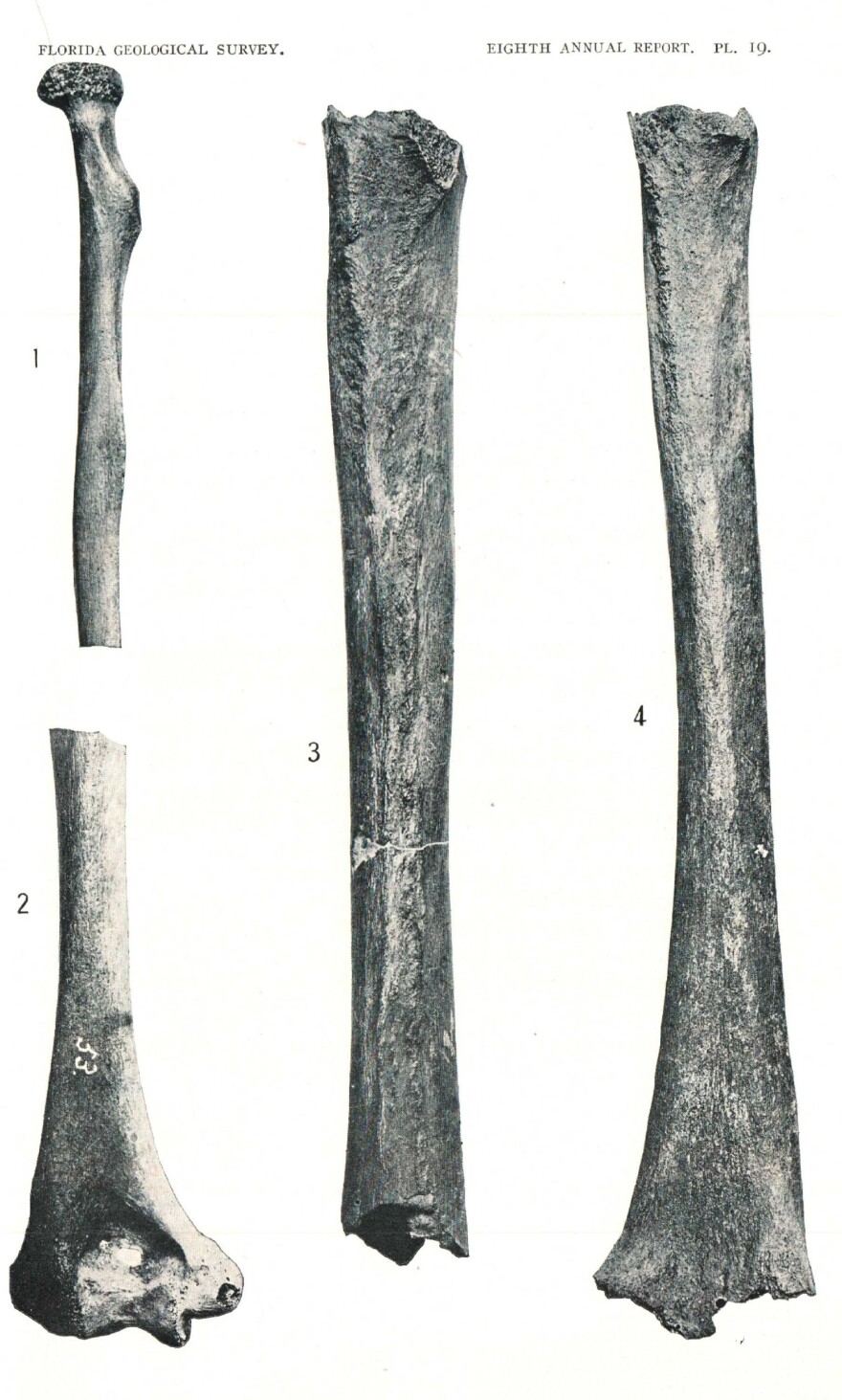

But in 1915, it was a spot that became world-famous because of the work of Elias Sellards, Florida's state geologist. Sellards led a scientific excavation of the site, where workers digging a drainage canal found fossilized animal bones and then, human remains.

Andy Hemmings of Mercyhurst University is the lead archaeologist on a project that has picked up where Sellards left off a century ago.

"Quite literally, where we're standing, they found what they, at the time, dubbed 'skeleton two' and 'skeleton three.' It turns out it's actually one individual, now known as Vero Man," Hemmings says.

The human remains were in a layer of soil that also contained bones from animals that lived in Florida during the Ice Age: mastodons, giant sloths and saber-toothed cats.

Sellards said this was proof that people lived in Florida during the Ice Age, at least 14,000 years ago. At the time, most scientists believed humans had been in the New World no longer than 6,000 years.

An anthropologist from the Smithsonian, Ales Hrdlicka, led the charge attacking Sellards' findings. Hrdlicka believed the human remains were of someone who lived much later and had been buried in the lower strata. Vero Man was discredited and became largely an archaeological footnote.

But in Vero Beach, Fla., a quiet community known mostly for its citrus groves, Sandra Rawls says the site of Sellards' investigation, and its potential, was never forgotten. Several years ago, Rawls and others in the community formed a nonprofit group, the Old Vero Ice Age Sites Committee, or OVIASC.

"There were a lot of people who still remembered and knew a lot, are interested in the site. Many citizens had dug here, almost like a public park. Tons of fossils are in private collections that came out of here," Rawls says.

The group helped stop a water treatment plant from being built on the site and began raising money to fund a new archaeological investigation. That's when Mercyhurst University got involved. Archaeologists from the school are in their second year of work at the site.

Backhoes have dug a large pit to remove several feet of soil. A 24-by-60-foot tent now protects the area. Inside, under Andy Hemmings' direction, several college students are painstakingly beginning work on a layer of soil that was on the surface during the Ice Age.

"We don't even use shovels. You see spoons and trowels right now, very delicately trying to keep track," Hemmings says. "If there's interesting objects in them — bones, artifacts — we want to know where they came from."

In the first year, the dig uncovered a human artifact they believe dates back at least 11,000 years. But on a lower level, the crew uncovered charred remains of a dire wolf and an extinct horse.

Hemmings says it suggests people lived on the site even earlier, at least 14,000 years ago. "Our supposition is that all this burnt material did not arrive naturally, that it really is from a hearth, that it is people burning and cooking on this landscape," he says.

Those are preliminary findings, not yet published nor subjected to the rigorous peer review process. In the past, many similar claims have been later debunked. If the findings hold up, the principal investigator at Vero, James Adovasio, says they will help rewrite what we know about early man in the Americas.

"Vero becomes one of the earliest evidences of a human presence in the entire state of Florida, substantially older than it was thought to have been. It probably represents a lifestyle that we know very little about," Adavasio says.

Over the last few decades, archaeologists have uncovered other sites that have pushed back estimates of when humans arrived in the New World.

But so far, none of the oldest sites have yielded what many consider the smoking gun — human remains. John Shea, an anthropologist and expert on early man at Stony Brook University, says positively dated human remains would change a lot of minds.

"The bar is set high, but there are people looking for these things," Shea says. "The more they look, if there are genuinely fossils out here from this time period, they will find them. If they keep looking and they don't find them, well then, you know, one has to accept the hypothesis that maybe they aren't there."

That's one of the things that makes Vero so intriguing. Researchers believe there's the possibility that human bones could be found there again and dated conclusively to that early time period.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxODg3MTg0MDEyMTg2NTY3OTI5YTI3ZA004))