Universities across the country are reckoning with the debt they owe the slaves who built their institutions and worked there. While the Community College of Baltimore County was established nearly a century after the Civil War, it too is coming to terms with the history of slavery on the land that is now its Catonsville campus.

There are the typical modern buildings and parking lots you see at any community college. But there also are reminders of the past: A stone farmhouse built in 1819. The Hilton Mansion, built in 1828. Both built by slaves.

Michelle Wright, a professor of history and Africana studies, said she uses those buildings to teach her students the history of the land.

“They’re shocked, and especially when you talk about the mansion because that’s the first thing you see when you drive up the hill,” Wright said. “And you say, you know, that was the big house. That was the house where the owners lived.”

Through its history, the plantation bred thoroughbred horses. It also grew tobacco as well as timber to fuel iron furnaces. The slaves worked there as well.

Wright said, “I think it’s kind of fascinating that many of the enslaved men were making some of the things that would further enslave them, like the collars, the slave collars that they had to wear with the bells or the spikes on them, they were making those. They were making some of the shackles.”

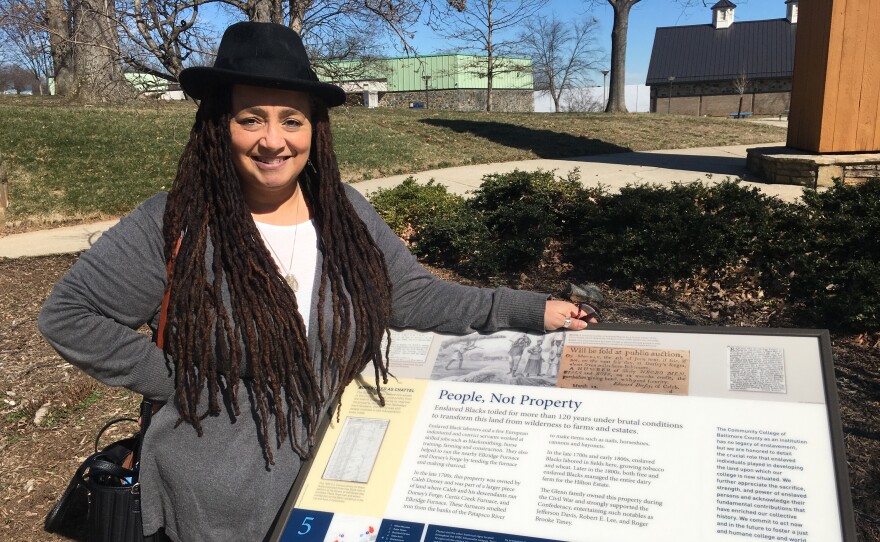

When you walk around the heart of the Catonsville campus, you find markers that explain the history. Wright pointed out one, called “People, Not Property,” that tells how for more than 120 years enslaved Blacks worked the plantation for 13 owners.

“We do walk upon this land,” Wright said. “This history, it really isn’t invisible. You can actually look at it. You can actually see some of the things that were built and you can imagine some of the stories.”

Long established universities like Brown, Georgetown and the University of Maryland have direct ties to slave labor.

“We do not of course, but our region has a history with slavery,” said CCBC President Sandra Kurtinitis.

She said the interest in the history of the Catonsville campus was sparked by the $7 million renovation of the Hilton Mansion several years ago, turning it into offices and an honors lounge.

“So it was natural for us I think to turn to our faculty who are, you know, this is their world, they’re historians,” said Kurtinitis. “They really began to dig into the history of the site.”

CCBC is a member of Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium of nearly 90 schools based at the University of Virginia. CCBC is one of only two community colleges in the project.

Other Maryland schools involved include the Johns Hopkins University, Towson University, Goucher College, Loyola University Maryland and the University of Maryland. People in the consortium compare notes on how they are addressing their institutions’ histories of human bondage and racism.

“We thought, what can we do so that this isn’t schools doing this one by one, siloed off on their own,” said Kirt von Daacke, the managing director of Universities Studying Slavery.

“This isn’t all the business of apologetics,” von Daacke said. “It’s also the business of we’re educational institutions. I think what’s really cool about all of these, even at community colleges, students are often involved in doing some of the hands-on research and learning actively.”

Students like Clara Weaver, who is 19 and will graduate from CCBC with an associate’s degree in general studies this spring. She’s been part of the school’s invisible history project, which researches the history of the land, including the enslaved people who worked it.

“It was really eye opening to me to just see how I’ve benefited from their labor,” Weaver said. “They built all of these buildings on campus and they kept the estate running which helped it to eventually end up in the college’s hands which let me go to college there.”

She said the invisible history project tells stories that either have been hidden or haven’t been told.

Weaver’s research includes telling the story of how Blacks played a critical role in the raising of thoroughbred horses on the plantation.

“Black horsemen really were the backbone of the thoroughbred racing industry,” Weaver said. “They deserve a lot of credit for that accomplishment.”