They look like vacation photos at first glance. Women in flowery kimonos gossip together in a circle. A boy on ice skates takes his first steps on a crowded rink. Two sumo wrestlers share a chuckle in the ring as a crowd watches on.

But behind the smiles, the same shadowy presence looms in the background: the tar paper barracks that housed the thousands of Japanese-American prisoners of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming.

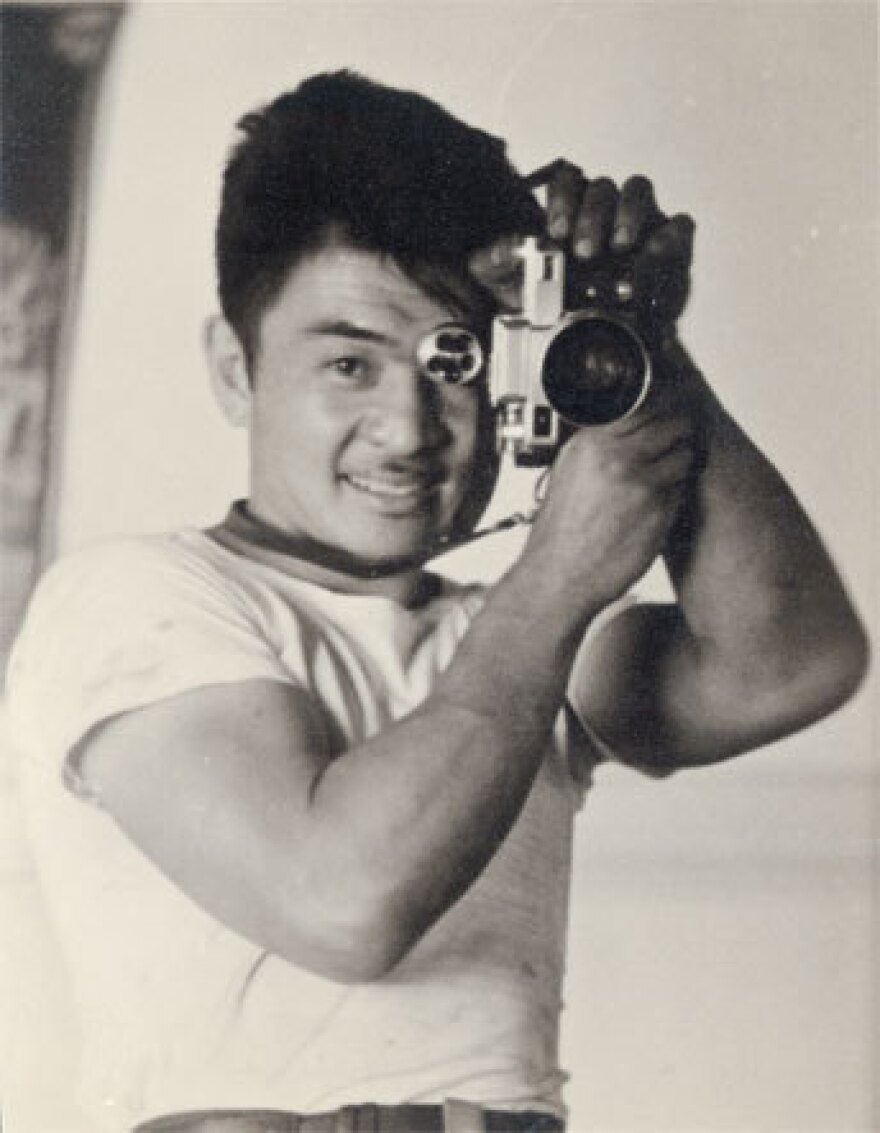

Bill Manbo, an auto mechanic from Riverside, Calif., took these photographs after he and his family were forced to move to a Japanese-American internment camp in 1942, just months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Seventy years later, Manbo's pictures are compiled in a new book, Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II, which was released today by the University of North Carolina Press.

The book's editor, Eric Muller, a law professor, has written two books about Japanese-American history during World War II. He says the photographs provide a unique glimpse of life inside an internment camp.

"Some of [the photographs] show quite a bit of happiness, joy and life, and that's really easily understood as a very moving comment on the resilience of the community, the ways they were able to create themselves some semblance of comfort and normalcy in a very uncomfortable and abnormal situation," Muller says.

When Japanese-Americans were first imprisoned during World War II, the camera was classified as a "weapon of war." Internees were banned from bringing cameras into camps.

But at some sites like Heart Mountain, local officials of the War Relocation Authority, the government agency charged with the internment of Japanese-Americans and other targeted groups during World War II, successfully argued to allow internees to take family snapshots.

Still, color photographs of the camps are rare, and Muller hopes these pictures will help viewers better connect with this period of American history.

"For me, black and white communicates a certain distance. You feel like you're looking at history," he explains. "I look at [the photograph of the women in kimonos], and I feel like I'm looking out my own window."

For Harumi "Bacon" Sakatani, who wrote an essay in the book, these color photographs capture familiar scenes from his early teenage years as a former internee at Heart Mountain.

"The colors bring back memories of the camp, whether good or bad," says Sakatani, who now lives in West Covina, Calif., and will turn 83 later this month.

Sakatani first learned of the Kodachrome slides of the camp from Bill Manbo's son, while helping to organize reunions of former Heart Mountain internees during the 1980s. He later showed the images to Muller because he knew of their historical value.

While the photographs show the everyday activities at the camp, Sakatani says they don't tell the whole story.

"[The photographs do] not quite show the injustices of what we went through," he explains. "My family of seven had to live in a room of 20 feet by 24 feet."

The camp's communal latrines and on-duty guards were also left out of Manbo's frame, Sakatani adds.

But some of the most poignant shots of the book are of Manbo's toddler son clinging to the barbed-wire fence surrounding the camp. These portraits provide a stark reminder that the families of Heart Mountain were prisoners of war.

When the Heart Mountain camp finally closed after the end of World War II in 1945, some internees, like the Manbos, had already left to relocate out East, and others, like the Sakatanis, decided to return to their homes on the West Coast. All faced the challenges of rebuilding their homes and careers, and seeking normalcy in life once more.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.