A visit with a Chilkat Ravenstail weaver, a rain-forest hike in search of Devil’s Club, the tale of a rudely awakened Black Bear, an afternoon with a fishing boat captain, a mountain jog with a champion ultra-runner, hair and make-up tips with a renowned drag queen, a sound-check at the home-studio of a Juneau-based hip hop musician, and a window into the life of a local poet and her 10-year-old son.

Special thanks this episode to Juneau field producer MK MacNaughton and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Transcript

Out of the Blocks: Juneau, Part 1

Multiple Voices: From WYPR and PRX, it’s Out of the Blocks: one neighborhood, everybody’s story.

We are perched at the edge of an ice field, which is footsteps from hiking mountains going out to glaciers.

We’re looking over at the state capital and the minor amount of hustle-bustle of downtown Juneau, and also looking out at the big cruise ships that pull in here during the summer and flood parts of downtown with people who are visiting.

For me, our town is so much more than our landscape. There’s this sense of kind of being stuck with each other that creates this bond between us, you know? I like to say that we belong to each other.

From producers Aaron Henkin and Wendel Patrick, with field producer MK MacNaughton, Out of the Blocks: Juneau, Alaska—right after this.

Lily Hope: There isn’t a lot of sound when we’re weaving except maybe the pull of the wool on wool. [speaking in Tlingít] My name is Lily Hope. I am a Chilkat and a Ravenstail weaver in Juneau, Alaska. I am Raven T’akdeintaan from the Snail House. I come from both Man’s Head House and Snail HouseHere on the loom we have a Chilkat blanket in progress. It starts with a Ravenstail pattern. We have Chilkat motifs—a profile face, some eyes, some split u-shapes that are all familiar in northwest coast art, but they have been slightly adapted to be weavable so we don’t go nuts while we are weaving. It is hours and hours and hours. One square inch of Chilkat weaving can be upwards of three hours in the making. The little fringes are decorated with 22 magnum bullet shells and when they are moved, the fringe—you know—they move next to each other and have this rain-like sound. We spend two years growing these babies, I like to say. It’s almost like a surrogate, and then this little being is cut free from the frame where it was woven and placed on the shoulders of a dancer and it’s really like watching your child take its first steps. My mother was Clarissa Rizal. She was a renowned regalia-maker and artist weaver in her own right. She passed away about three years ago and she was constantly teaching and I had no idea. For the twenty years leading up to her passing, she was always invited me to, you know, “Stir this dye pot. You wanna see how this blue comes out? Isn’t this cool? Oh, look, we’re gonna go harvest bark. You wanna come with me and do this thing?” You know, and every time I was like, “Sure, I’d love to hang out with you. That’d be really fun. Sounds like a good adventure.” And then she passed and I was halfway through my first Chilkat blanket and I was like, “Wait, hold on, don’t go yet. I’m not quite ready.” And I had to be ready because she left. It was a good six weeks after she passed and I sat down to weave and I put my hands to the warp and grabbed some weaver strands and I broke down and I couldn’t. I couldn’t move. I was like, “How am I supposed to move forward without her?” I called a friend and I said, “What do I do?” And he said, “You go to the backside of your loom.” Chilkat weavings are the veil between our physical and spiritual realms. When we go to the back of the loom, that’s the closest us humans can get to that ethereal realm, to the spirit world. And he said, “Why don’t you just sit on the backside of the loom and put up all those little ins in the back with your needle and see how that feels?” Four days later of putting up all those ins because I had half of a robe finished and all the little ins needed to go up. On that fourth day, I had this waterfall, almost like a river of emotion and memories of my mother and I throughout her whole life from my birth to her passing. All of those rushing through me from the back to the front, into the robe itself and I just cried and cried and cried. And then I cleared up and took a deep breath and went, “Oh, now I can weave. I know what I’m supposed to be doing.”

Jason Boone: Some days, we have six giant ships in here. It stimulates an incredible economy, you know? It’s just thousands and thousands of people from May 1st to October 2nd coming into town on a daily basis. My name’s Jason Boone. I work for Juneau Tours & Whale Watch and I sell tours to all these wonderful cruise-ship passengers that dump off the ships every day. [speaking in the background] You want to go out to the glacier, maybe go whale watching, do something fun today?

Pat Delahunty: Nah, we’ve done all that. I’m just hanging out, going to the Red Dog, you know?

JB: Okay. Red Dog Saloon. That’s a big attraction here.

PD: Yeah, it always is. Yup. Pat Delahunty. I’m from near Riverside, California. We got here at 7:30 this morning, we leave about 10:00 tonight, so it’s about 14 hours in Juneau. This is one of our longest stops. From here, we got to the Tracy Arm, so we see some glaciers in the ship. And these ships are neat because they can position themselves so you can see a glacier or two of them, and they can rotate the ship around so you don’t even have to leave your state room. You can sit there in your room, on your patio and enjoy your breakfast or a drink or whatever and watch all the scenery go by you.

JB: The cruise ship passengers… I only get a glimpse of them. But the migrant workers that come here? I’ve met some of my best friends in the world, you know? We’ve experienced such incredible things together—the Northern Lights, I’ve taken airboat rides around glaciers, I’ve seen bears and eagles and things that people just dream of seeing. My story? I lost everything in a natural disaster, in a tornado in Florida. So, I kind of picked up the pieces of my life and then all of a sudden I had this opportunity to come to Alaska and work and hey, why not?

Aaron Henkin: Talk about how much longer you’re gonna be here this year and where you’re headed next.

JB: After I leave Juneau, I’m going to visit some friends in Colorado, visit some friends in Vegas, visit some friends in California. You know, I’m not in a rush to get back to Florida, but when I do get back to Florida I hope to have a margarita and be on the beach for a little while before I then go to Savannah and do another work gig.

AH: What street is this that your booth faces out onto?

JB: I’m right here on Franklin Street. They call me the “t-shirt company booth” because I’m right here in front of the t-shirt company.

AH: This entire stretch, many blocks in a row, is like one giant gift and souvenir shop.

JB: Oh, absolutely. And not to mention all the jewelry stores. But a lot of this just becomes a ghost town as soon as the cruise ships leave October 1st and October 1st is my date out of here as well! We’re all out of here. We’re all going on vacation and on new adventures. We’ll be back next year.

Stacy Eldemar: For me, my neighborhood is mostly this. Outside, where I have this amazing rain forest that we live in. We have this awesome blanketing mattress of moss-covered ground that’s always soft underfoot, where I can just hear nature being what it is. My name is Stacy Eldemar and we are at the Mendenhall Glacier in the Tongass National Forest. The Tlingit, my tribe, called this “sítʼ,” which is the word for “glacier” and we are walking a trail where the glacier once stood thick, thick, thick. The glacier has receded a mile and a half in my lifetime. I judge it by the rock outcrop and the ice was on the rock outcrop when I was young. And it’s really hit me in the last decade where I’m seeing it like a dying grandfather. I consider the glacier my oldest, dearest, most trusted friend and to see it dying is heartbreaking. That said, perhaps it is time for this glacier to die, and it will come again in my tiny miniscule blink of a life. That brings me comfort. But I am looking for devil’s club. Devil’s club has many purposes. In the old ways, devil’s club would be mounted above the entryways of doorways and essentially does not allow any bad spirits into the house because the thorns will essentially grab any of the bad spirits and will not allow them into your house. So, in the fall I harvest a devil’s club stock from the woods. It serves as a protection, a reminder to be mindful in where I am and becomes part of my venturing meditation. And I think we’ll go ahead and take this and… As much as… Don’t handle devil’s club with your bare hands. I still like to feel if it’s friendly towards me and this one is…and raven approves. And then this is where the leather glove comes in. [inhales] That smell is marvelous. [speaking in Tlingit]

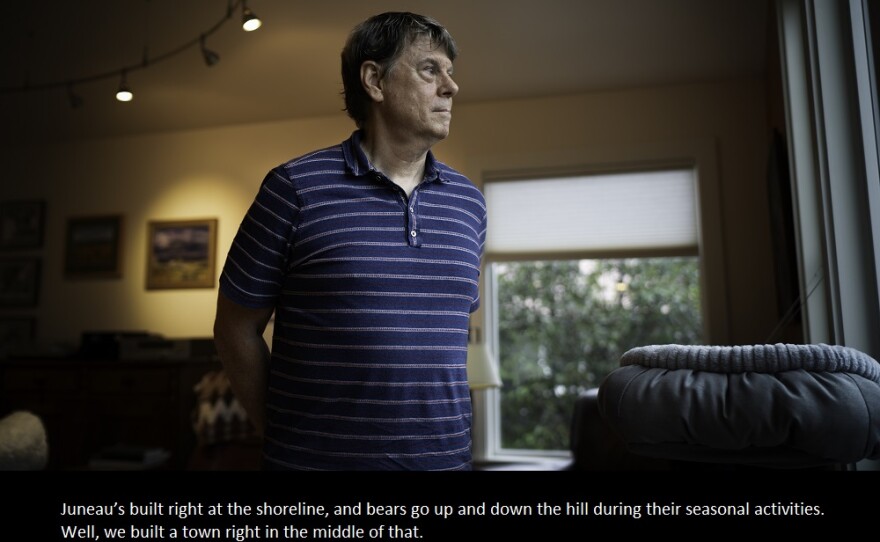

Matt Robus: My name is Matt Robus and we’re in my living room here in Juneau, Alaska. When I retired, I was the director of the Division of Wildlife Conservation, the Alaska Department of Fishing and Game. Juneau’s built right at the shoreline and bears go up and down the hill during their seasonal activities and they go up on the hill for grass in the spring, they come down to the creeks and shore early in the year, and then mid-slope for berries, and then they hit the streams for salmon… Well, we built a town right in the middle of that, so they are forced to come into close contact with people multiple times through the year. But when you have them in the center of a community, eventually, you know, something needs to be resolved and we had a bear in a neighborhood and eventually we got a call that this bear was up in a tree, asleep. An assistant and myself rolled out there and got out of the truck and sure enough, there’s this bear and it’s probably up about twenty feet in the tree. And I loaded a dart and got ready to immobilize it, knowing it would fall out of the tree… But black bears are amazingly tough animals—they just kind of bounce off of things and usually are okay. As I got ready to raise the gun and take the shot, I realized there were kind of a line of people from the neighborhood standing behind us and I asked them to stand clear or whatever and one of them piped up and said, “Isn’t that bear going to fall on the ground after you dart it?” And I said, “Well, yes.” “Well, will you give us ten minutes and we’ll all go to our houses and get mattresses and we’ll come out and make a pile of mattresses on the ground underneath the bear?” And sure enough, within fifteen minutes, we had this big pile of mattresses underneath this tree and the bear’s still asleep. So, I darted the bear and when that dart hit into the front shoulder, the bear was really startled and it stood up on the branch and then it became evident that that bear had been there a long time because the first thing it did was it started peeing. And it kept at it for a good, long time and all these people who had been just starry eyed a moment before were starting to react to what was happening to the mattresses that they had put under this bear. My assistant and I are standing there, facing away from these people, just going, “Oh God, oh God, what are we going to do?” And the bear finally went to sleep after six or seven minutes, tumbled down, hit at the edge of the mattresses, so they might have done some good… And usually when you approach an immobilized animal, you do it very carefully and you probe them a time or two to make sure they’re not going to come at you. This time, we each just grabbed a handful of fur and ran and threw it in the pickup truck and booked out of the neighborhood. But that was kind of the moment I remember in my career where I was like, “This can’t be happening, but it is.” Like, what are we gonna do? So, there you go. One of the things that strikes you about that whole deal is that you think you’re going into a profession where you’re going to be dealing with animals all the time and, in fact, most of wildlife management is dealing with people, one way or the other. Basically, we humans create the problem and the bears usually suffer for it. So, it’s a checkered, confusing thing to deal with.

Bonny Millard: So, he’s gonna want to deliver his fish because this storm is coming in. So, he’s gonna tie up, I’m gonna start the boat, we’re gonna get his fish…

AH: So, what are we looking at here in this bag?

BM: Okay, these are cohos and the weight on it is 228 pounds.

MB: My name is Mark Butchkoski.

AH: Is this boat a regular stop for you for to… Tendering is what’s going on here, right?

MB: Yep.

AH: What do you got there? That’s you’re…

MB: That’s the paperwork.

AH: And that tells you what?

MB: That tells me it was a bad day of fishing. [laughs]

AH: I mean, to someone like me, 220 pounds is pretty impressive. That’s not?

MB: You’re putting that on the air?

BM: I’m Bonny Millard and we’re in Juneau, Alaska. We’re on the fishing vessel San Juan, which is my boat. It’s a 48-foot delta. I commercial fish with it and I also tender.

Man on radio: Hey.

BM: I got you Bob.

Man on radio: Yeah, don’t bother looking for me, I just… The few I have on board, I’m not gonna worry about but I might go back out tomorrow or the next day.

BM: Okay, well just give me a heads up if you do, Tim.

Man on radio: Roger that. I’ll talk to you later.

BM: So, the gillnetters will go out and they fish for salmon, and then it’s up to the tendermen to come and get their fish so that they can continue fishing. So, the tenderman gets the fish and then takes them back to the plant and these days, we try to make that happen every other day so the fish is really fresh when it hits the market.

AH: Today, you’re tendering. Other days, you’re going out yourself and you’re doing that longlining and you’re filling up your own hull with your own fish.

BM: Yeah, tendering is not fishing. But I’ve had to diversify to keep this boat working because a boat costs a tremendous amount of money. I always laugh because I’ll be working on my boat, I’ll have my coveralls on and everything and somebody walks by and just goes, “God, your boat looks amazing!” And I think, “Well, what about me?” If I spent this kind of money on myself, I’d look really amazing! But I spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on this thing. [laughs] So, I always think it’s pretty funny. It’s just a tremendous amount of work.

AH: Tell me your husband’s name.

BM: Pat Millard. I met Pat… So, my boat motor were running and his wasn’t running, so he said, “Why don’t you take me out fishing?” And I said, “Well, if you’re gonna go out fishing, you’d better be at the dock at 4:30 in the morning. Otherwise, I’m leaving.” So, anyway, there he was and we went fishing together that day and that was it.

AH: As they say, he was a keeper.

BM: He was a keeper. Yes, he was. So, when we trolled… We troll for salmon off the coast of Alaska and we had just gotten done with a big trip and the hold was full of fish. And we were cleaning the boat up to head to town to unload to the cold storage, because when you go to town, you do your laundry, you do your grocery shopping, you take showers, you go out to dinner, and you know, it’s just kind of a fun time. So, it’s just all getting your laundry together and I was downstairs changing sheets and all that and when I came back up, Pat was nowhere to be seen and he fell off the boat and we never saw him. It just like… Four minutes. It just, like, vanished from the face of the earth. So, that really changed my life a lot. It was an overwhelming thing to go through.

AH: What was it like for you to head out on the boat solo after losing him.

BM: It was real emotional. A lot of time was spent on the ocean and of course it’s just beautiful out there. You know, it was pretty teary-eyed a lot and I didn’t know what I was doing half the time. But you’re there so you just have to do it. So, that’s how it worked.

AH: And you’ve been doing it on your own for how long now?

BM: I think almost forty years. Oh, my goodness. Yeah.

AH: What an interesting relationship you must have with the water. I mean, the water is what brought you and your husband together, the water is what took your husband from you, the water is how you make a living. Talk about your relationship with the see.

BM: I love the ocean. Sometimes, when it’s just terrible—blowing and raining and rough and everything’s breaking and everything—I just think my love affair with the ocean is over. Now! But there I go, back again. So, I’m constantly… Mother Nature and I, we have an agreement, you know? We like each other. So, that’s a good thing. But the sea is… I really like the ocean. I never get tired of it.

Multiple Voices: It’s Out of the Blocks: Juneau, Alaska. One neighborhood, everybody’s story.

Jeff Roes: Anger, fear, confusion, elation, happiness and joy, sadness, excitement, frustration… There are times where I go weeks or months without noticing the rhythms that my body’s making through breathing or my footsteps or anything when I’m running, and then there’s other times where I’m really focused on one or the other of those things. But it often, for me, running up and down. If I’m going up a steep trail or down a steep trail, I feel like I can kind of use it as a tool to get into a place mentally and psychologically where, suddenly, what I’m doing doesn’t feel physically difficult anymore. I’m Jeff Roes and I’m an avid mountain trail, long-distance runner. When I was racing, I was specializing in fifty and hundred mile distances. It was really what I focused on and I don’t run that far anymore. And the main reason I don’t race anymore is that you really need to put most everything else in your life on hold to be prepared to do it on the level that I was trying to do it, as high of a level as possible and… In terms of time that it took up, it was at least forty or fifty hours a week. Two years in a row, I was voted North American Ultra-Runner of the Year, which I’m proud of. I don’t need to downplay it but it certainly wasn’t why I did it, but I had a lot of success in the sport, especially at the hundred-mile distance. I was able to do quite well in most any races that I ran. Of the races I’ve done, my finishing time has ranged between fifteen hours and twenty-five hours for a hundred miles. You might feel horrible for six or eight hours in the midst of a run, but the larger picture of the entire run if it’s a fifteen or twenty-hour race… You might have a great race in which you feel horrible for several hours and still have a really great race. You know, sometimes, the last mile or two of the race, I feel like I’m just, like, holding back tears the entire time. There’s just so much emotion in the accomplishment or in just being relieved that it’s done and I’ve had other times where I finish and I just kind of find the whole thing really humorous and I’m just kind of laughing as I’m crossing the finish line because it’s kind of a silly thing to do in some ways. And sometimes—every two or three races that I’ve done—I’ve not wanted it to end yet and there’s been a little bit of sort of a feeling of like, “Oh, I wish there was five more miles,” or whatever. I sort of started running long distances with this idea that it would be such a way to tap into my individual inner strength and power. But it has surprised how my main, deep, inner take-away from it has been kind of the opposite of that. It’s been how it connects me to other people and how it connects me to the land.

James Hoagland: My name is James Hoagland and I like to say that I create the illusion of Gigi Monroe. I will start with my foundation that covers a little bit of stubble and start to draw on the contours of a feminine face. Gigi Monroe is a drag queen. That’s my drag persona and as her, I create drag shows and mentor young performers. It’s, like, that two hours once a month that people can take and just enjoy a spectacle, you know, with all different kinds of acts and different kinds of music but something that allows them to just have a release. This is an interesting community for LGBTQ people because, like, in a lot of rural places, younger folks come out and leave. Lately, I’ve been doing a teal—kind of a peacock blue almost—color on my eyelid. That’s covered in the same color glitter so when I blink, it’s a very sparkly flash of peacock blue which is very exciting. I came to Juneau literally on a cruise ship. I was working as a costume supervisor for Norwegian Cruise Lines. So, every Tuesday from 2 PM to 8 PM I would be in Juneau. I was also single and I met a guy in port who I went out on a coffee date with and we started seeing each other every Tuesday from 2 to 8 that I was in town. And then at the end of the summer, I thought of just moving to Juneau and seeing what would happen with the relationship and as a drag queen and as a queer man in his early thirties trying to settle down. So, that was six years ago.

AH: Tell me what happened with that relationship?

JH: Three years ago, we got married. I’ll add fake lashes, I will draw on over-sized lips and that is my face. You know, we like to quote Dolly Parton by saying, “The higher the hair, the closer to God.” But I just always loved wigs. I liked all kinds of wigs. Every kind of color and texture, curly, straight, wavy. At some point, I realized that this was something that I taught myself so that I could do my own hair, but it was something that other queens really needed help with. So, I started just styling a few and then I would post pictures of them online, say that they were up for sale, and I would get instant sales. That’s grown into a full-time business today and I ship out thirty to forty wigs a month. This is my most popular design. As you can see, I’ve cut all of the hair off the base wig and then I pin on five ponytails. That means that I can get huge volume. And then, of course, the ever-important hairspray. There is a theme that runs through my whole life that is living at the intersections. So, whether it’s male and female, living here in Alaska, you know, the wilderness and the city. I’m really at the intersection and I can be a bridge. That’s my intention and I hope that that’s what I can leave this world knowing that I had an impact by being a bridge between communities and people.

Chris Talley: My name is Chris Talley, also known as Radiophonic Oddity or RPO. We’re currently in my home studio or my bedroom, you know? Got the business license but also got the bed in the corner, you know? I’m a rapper, I’m a beat-boxer, I’m an actor, I’m really just an entertainer. [rapping in the background] This is an Everlast Choice of Champions bag made in the U.S.A., of course. Red and black stripe.

AH: And this is where you take out your aggression and get a little exercise in the process?

CT: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. I’m not going to lie, I used to do that on my door and then my parents started to get mad at me.

AH: What do you know about your birth parents?

CT: So, basically, what I do know is both my parents are actually dancers, so they started off kind of, like, entertaining people, doing all that kind of stuff in high school and college, and then they both kind of hit a heavy slope. My dad started selling drugs and my mom started doing drugs, and one thing kind of led to another, you know? My mom usually wouldn’t pay, you know, with money to get drugs from my dad, so that’s kind of how I came about. They didn’t really have the means to take care of me. You know, they both had children on their side and they just decided, you know, just kind of give me up for adoption. I was born prematurely, so I was born in kind of critical condition, kind of critical care for a while, but I was adopted by some lovely people. I believe my parents had just moved to Alaska—an all-white family, you know—and they were looking for kids who were up for adoption, like, you know, newborn babies. So, basically, they were calling, asking the hospital if they had anyone up for adoption. They didn’t have any babies, you know, healthy babies that were up for adoption but they just had a premature black baby that was just born and they rushed up to the hospital right away. It’s actually kind of funny. When they were on their way to the hospital, they got into a car accident. A truck ran them off the side of a road and the car flipped over maybe five, six times. After all that happened, the truck drove them to the Anchorage hospital where I was being born and, you know, they look really disheveled. They just got into a car accident and so they were like, “Are you guys sure you’re up to adopting this baby?” And they’re like, “Yes! We’re sure! We’re positive!” So, they got me and I’ve been in their loving care ever since. I couldn’t ask for a better family, really.

AH: I wonder if you ever think about, like, how life would have turned out for you if you hadn’t been adopted.

CT: I actually do think of that sometimes. I would imagine that my life would have been very lonely, you know? I feel like it would have been a lot of self-reliance, but I don’t think I would have turned out very differently, honestly. I feel like I kind of would have stayed the same. Yeah.

Christy NaMee Eriksen: My name is Christy NaMee Eriksen. I’m a multidisciplinary poet, teaching artist, and community organizer. Right now, we’re sitting in my home in what I call the “out the road” of downtown Juneau. So, it’s still walking distance but kind of away from the beaten path a little bit, looking at the water.

AH: You’ve got the clouds clinging to the side of these pine-covered mountains. I can’t imagine ever getting tired of this view.

CNE: Yeah. I think things in our lives are generally a little bit cloudy, so I embrace a little bit of partly-cloudy weather myself. I grew up in Juneau. I was born in Korea but I was raised here. I moved for a little while. I went to school down south. You know, fell in love, did that… I was there for a little bit and then I returned to Juneau ten years ago. You know, I was pregnant, so I think when you’re pregnant you just really want to go home. And then when I got here, I just immediately tried to start bringing back the parts that had felt “home” to me in Minnesota, which is where I’d just come from, so that I could have the best of both worlds in the same space. Kindred Post is an idea born out of what was a historically downtown post office space closing about six years ago. I’m the daughter of a life-long postal employee—he actually retired as a postmaster—and so I’ve always had appreciation for the postal service. And I think that, you know, when I really thought about what a post office is I feel like at the heart of it is connection, right? It’s about sending something to somebody else and somebody else receiving it. And so, I opened Kindred Post and we continued to be a post office where we offer mail services, you can buy stamps and send packages and all of that, but when I opened Kindred Post it felt like a really natural thing to also invite a lot of poetry events into the space.

“When your brown son tells you over dinner he thinks he’s ugly. When you stutter on your own memories. When you reach for him, a table and a canyon away. His hair in your hands. A thousand falling stars. Each one, a wish that has already passed. You, the color of a good-luck penny. You, the color of harvest. You, the color of flight. Ain’t a ray of sun in the new world that won’t wanna shine on your face.”

AH: What’s your son’s name?

CNE: His Hispanic name is Diego and his Korean name is SunWoo.

AH: Are you raising him by yourself?

CNE: Yeah. I’m a single parent. I’ve been a single parent since he was about three weeks old. Yeah.

AH: He’s on his way home from school. He’ll be home here before too long.

CNE: Yeah, he’s on his way home. [speaking to her son] So, I forgot to tell you this was happening but I have a couple of friends here who are doing an interview. You want to be a part of it?

Diego: Hello. Nice to meet you.

AH: Good to meet you. Let me invite you to introduce yourself. Tell me your name and tell me how old you are.

D: I’m Diego and I’m ten years old.

AH: What do you want us to know about Juneau?

D: It’s great and really cold. Sometimes sunny, but I hate it when it’s sunny and sometimes I like it when it’s sunny. Sometimes, you could fall down and see birds above the sky and they’re swirling above you.

AH: You sound like a poet yourself. I think you just made a poem.

D: No, I didn’t make a poem! I just thought of something that happened. What was your favorite part of the day?

CNE: My favorite part of the day today. Thanks for asking. I really loved my walk to work today because on my way to work, my phone died and so I put it all away and then I just walked to work listening to the sounds of everything around me. And for some reason, I don’t do that often enough. It felt really good.

D: Cool.

Multiple Voices: You’ve been listening to Out of the Blocks, from radio producer Aaron Henkin and music producer Wendel Patrick. Special thanks to field producer MK MacNaughton and KTOO Public Media. Aaron and Wendel want to thank all of us who took a leap of faith and shared our stories and our lives. For WYPR and PRX, this is Juneau, Alaska signing off.