Many things embarrass me, but reading isn't one of them.

I'm not ashamed of my slightly weird collection of prison memoirs. Nor the flaky meditation books. After all, I can pretend I never read those.

My guilty pleasure is at the foot of the shelves, hidden in shadow. It's this: volume after volume of possibly ghoulish, probably macabre, thoroughly entertaining obituaries.

The pleasure I get from reading obits is a little creepy — there must be something amiss since I can't imagine doing it at a cafe, which is perhaps a good test of a guilty pleasure.

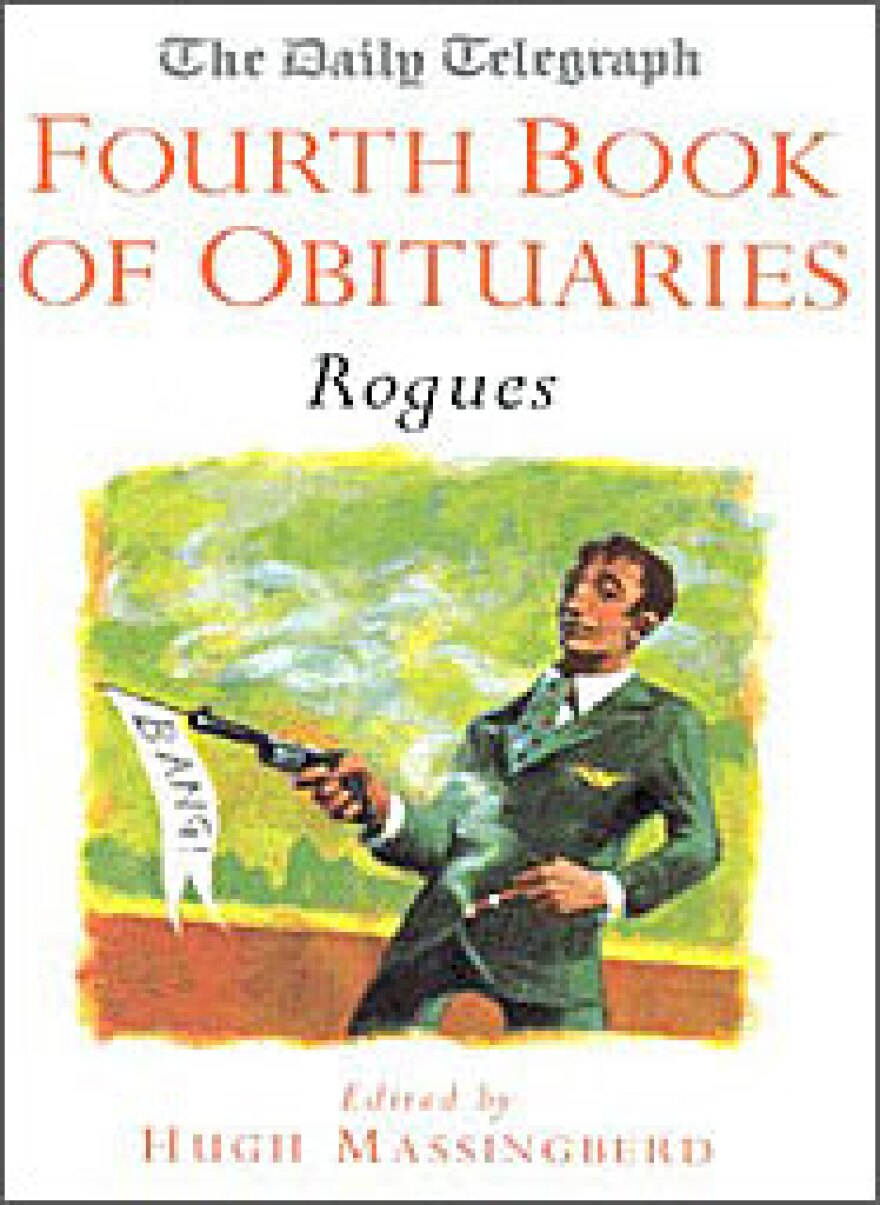

Of all the obit books, my favorite is The Daily Telegraph Fourth Book of Obituaries. Its subject is rogues, and it combines an English affection for eccentrics and an English fascination with the slightly perverse and the very drunk.

There's an obit about a brothel-keeper from Marseille who ended her days "toothless save for one rotting fang"; an Australian politician who "gained nationwide notoriety for his keenness to enter beer-belly competitions, his habit of stirring his tea with his finger, and his regular nomination as one of Australia's worst-dressed men," plus a low-life writer whose penchant for booze was so pronounced that, when commissioned to write an autobiography, "he had to place an advertisement asking if anyone could tell him what he had been doing between 1960 and 1974."

A common defense among obituary-fanciers such as myself is that the obit is not about death at all. It is about life. This is true since an article about the condition of deadness would make for turgid reading at best.

Yes, an obituary is a record of a human being condensed and terribly reduced. But it's also a tale from start to finish: a complete life, whole in a way that, ironically, its subject can never see.

The obit is as close as news gets in structure to the short story. After all, how many other news articles have a conclusion? An obit also shares with literature a talent for the revealing detail, as in The Times of London obit of Cyril Connolly, which delightfully describes the intellectual's "habit of marking his place in a book at the breakfast table with a strip of bacon."

During my past career as a journalist, I relished writing obits and equally dreaded phoning relatives for the necessary facts. But to my surprise and great relief, they often wanted to talk — they wanted their recently deceased loved ones recorded in print.

Those rogues in The Daily Telegraph Fourth Book of Obituaries had more to confess than I ever have. Still, when I close that book, a grin on my face, I'm the one who ends up looking guilty.

My Guilty Pleasure is edited and produced by Ellen Silva.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.